Jailed Lula holds key cards in uncertainty over Brazil election

15/05/2018

by Joe Leahy

Originally published on the Financial Times

Frail economy and crime stir populist voices ahead of October poll

Even from his jail cell, Brazil’s former president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, founder of the Workers’ party, which has led Brazil for 13 of the past 15 years, still holds some of the most important keys to Brazil’s elections in October.

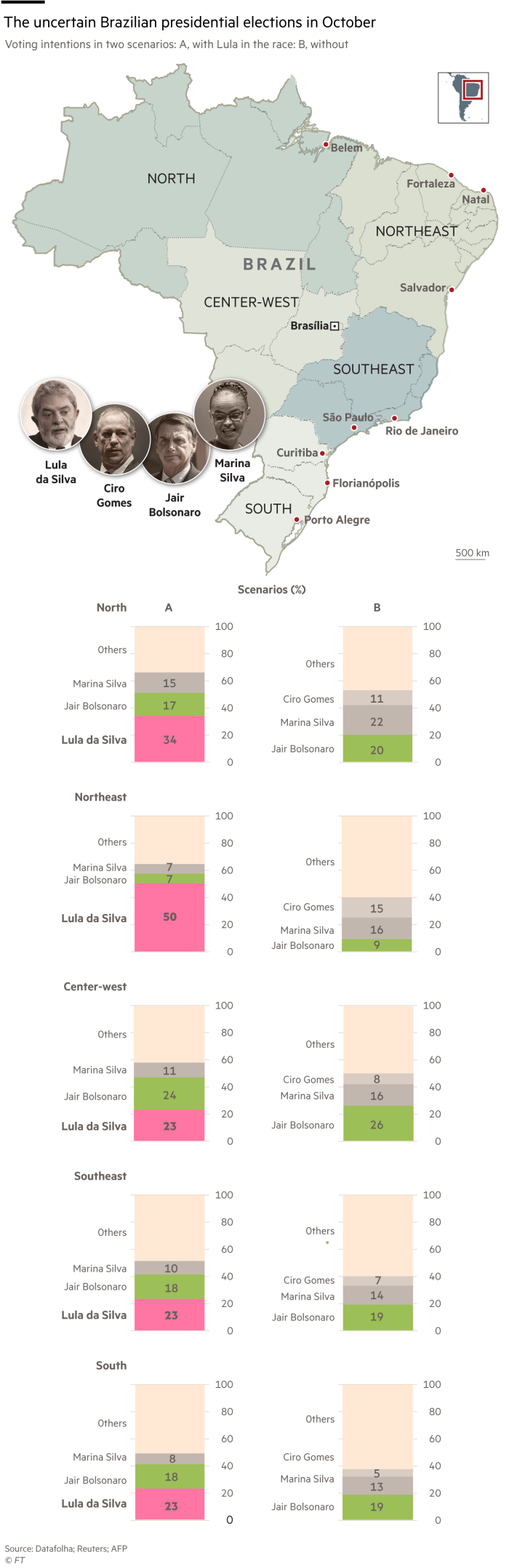

Lula has been ahead in early polls in four out of five of Brazil’s main regions (see map below) in spite of being imprisoned in April on corruption charges. There remains a chance that he may still decide to run, though this will not be clear until the mid-August deadline for the candidates for the presidency finally to declare.

Even if Lula opts not to run — or is blocked by the electoral authorities because of his criminal conviction as seems likely — his still immense popularity could make any endorsement he gives critical to the chances of Brazil’s left, which has been fragmented by corruption investigations.

At a recent conference in London, Luís Roberto Barroso, one of Brazil’s increasingly outspoken new crop of supreme court justices, seemed to summarise the age-old problems afflicting Latin America’s biggest country.

“We still live in a country in which, perhaps as a result of slavery, there is a belief that there exist inferiors and superiors,” Justice Barroso told the Brazil Forum UK. “Since there are not rights for everyone, each goes in search of their own privileges.”

Yet this is changing. The judge was speaking in the same week that he and his colleagues on the Supreme Court took a key step towards removing the so called foro privilegiado, which in effect has granted many politicians immunity from prosecution.

The ruling comes in a year when the country, perhaps more than at any other time since the end of the military dictatorship in the mid-1980s, finds itself at a political crossroads.

The uncertainty over Lula’s position aside, October could well see the election of a president who, for the first time, comes from outside the established parties that have ruled since the early 1990s.

This is the first election, notes Chris Garman, analyst with the Eurasia Group political consultancy, where none of the leading candidates “who have the advantages of television time, money and party support” are really hitting home as far as the demands of voters are concerned. In short, the result remains up in the air.

In Lula’s absence, the frontrunner appears to be the far-right congressman and former army captain Jair Bolsonaro. Until quite recently, his taste for guns and authoritarianism made him something of a political pariah, though his campaign appears to be capitalising on Brazilians’ fear of crime.

With about 60,000 people murdered in Brazil last year, the Brazilian Forum of Public Security and the Instituto Igarapé, two security think-tanks, report a prevailing dread among Brazilians that they will be the victims of homicide. As such, Mr Bolsonaro’s pledge to change the law to make it easier for citizens to bear arms is striking a popular chord.

Next in line is environmentalist and former minister Marina Silva, who comes from a rubber-tapper family, while Ciro Gomes, a veteran but maverick politician from the left, is polling quite well.

Apparently trailing are a number of more traditional candidates. Geraldo Alckmin is the former São Paulo governor and head of the centre-right Brazilian Social Democracy party (PSDB). Others include the current president Michel Temer and former finance minister Henrique Meirelles.

Just where such contenders stand in the running should become clearer when the official campaign begins in August. Meanwhile, the electoral fate of Manuela D’Ávila, who runs for the Communist party, may depend on what Lula decides to do.

Against the backdrop of uncertainty, “this election is going to be a real test case for what factors drive presidential elections,” says Mr Garman. The economy is clearly expected to be one. After suffering its worst recession on record, Brazil has undergone a brutal currency depreciation, rising unemployment and cuts in government spending. As a result, inflation has declined to levels not seen in 19 years and interest rates are at record lows.

“Thanks to a classical adjustment”, says Walter Molano of BCP Securities in a research note, Brazil has transformed itself “from the sick man of Latin America to the picture of good health”.

Agribusiness, arguably Brazil’s most globally competitive industry, thrives thanks to China’s seemingly insatiable appetite for food.

“As fast as [Chinese] demand for meat will grow, demand for grain will grow even faster,” says Gersan Zurita, senior vice-president at Moody’s Investors Service in São Paulo.

Still, the story of Brazil in 2018 remains more one of as yet unrealised potential. Industries such as mining continue to struggle. “We have a huge availability of natural resource that we should be able to exploit more,” says Tito Martins, chief executive of zinc miner Nexa Resources.

The October presidential election is key to the revival of Brazil’s economy, say analysts. One important question is whether the winner will be able to implement important fiscal reforms, such as overhauling the pension system, to rein in a fast-growing budget deficit.

This has become even more important given rising US interest rates, which are set to tighten monetary conditions in emerging markets, including Brazil.

The establishment centre-right parties including the Brazilian Democratic Movement of President Temer and Mr Alckmin’s PSDB are seen by markets as the more reliable economic managers.

But they have been discredited by Lava Jato, or Car Wash, Brazil’s sweeping anti-corruption investigation, that has implicated past and present living presidents and a chunk of congress.

People abroad “tend to see Brazil in a negative way because of the multiplication of these corruption scandals”, says Sérgio Moro, a judge and one of the leading figures in the investigation. “But in my opinion the correct way to see it is exactly the contrary,” he adds. “Brazil is dealing seriously with the problem of corruption.”

The elections are fraught with economic risks, say some analysts, among them that a populist might win. Mr Bolsonaro, for example, admits little knowledge of the economy. He has promised to rely on advisers, among them respected hedge fund manager Paulo Guedes, but has scant record of pushing through legislation in Brazil’s fractious and pork-barrel loving congress.

Mr Bolsonaro is in a group referred to by Mr Garman as the “quasi-reformers”, which also includes Ms Silva. They appeal to voters’ desire for clean candidates seen as likely to be tough on corruption, but their lack of congressional support in and unproven negotiating skills could make it difficult for them to pass reforms. Ms Silva has economic advisers from the centre-right but she has lacked punch in previous elections and analysts doubt her ability to negotiate with congress.

Markets anticipate a “pessimistic” electoral outcome, says investment bank Nomura in a research report, with the result likely to be a government ill-prepared to push through reform. For the man or woman who becomes Brazil’s next president, therefore, growing an electoral base is only the first challenge.