Brazil’s Crime Costs Double in Two Decades to More Than $75 Billion

11/06/2018

By David Biller and Flavia Said

Originally published on Bloomberg

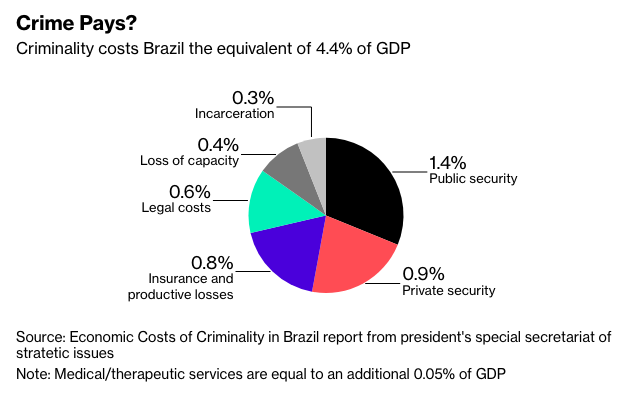

Crime now costs Latin America’s largest economy over $75 billion a year, double the amount of two decades prior, and efforts to combat its spread have had only “limited” effect, according to a government report published on Monday.

Brazil lost 285 billion reais to crime in 2015, up from 113 billion reais in 1996, according to the first-ever report released by the federal government on the issue. The total cost of public security, private security, insurance, imprisonment, productivity losses, as well as associated legal and medical costs now eats up 4.38 percent of GDP. Evidence shows that the cost has only risen since.

As the murder rate continues to rise, neighborhood shootouts, bloody prison riots and shocking instances of street crime dominate Brazilian news media, pushing the issue of violence higher up the list of voter concerns ahead of October’s elections. Constitutionally, public security is the responsibility of the states rather than the federal government, but rising crime rates has forced the administration of President Michel Temer to act, primarily by dispatching the armed forces to command security in the state of Rio de Janeiro until the end of the year.

On Monday afternoon, Temer used the launch of the report to announce the creation of a single system of public security, to improve coordination between municipal, state, and federal crime-fighting agencies.

“We don’t want to interfere with states’ areas of responsibility,” he said. “But we want to ensure interaction on public security with all Brazil’s states, via coordination that can only be facilitated at the federal level.”

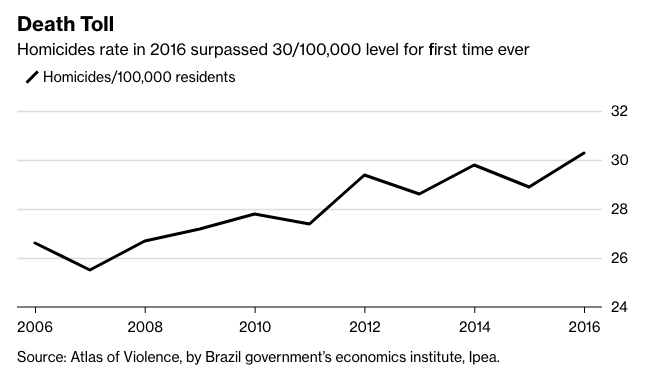

The report states that substantial increases in public spending have provided only “limited” social benefits, citing growth in homicide statistics. Brazil registered 62,517 homicides in 2016, meaning the murder rate has crept over 30 per 100,000 for the first time ever, according to data released last week by the government’s economics institute, Ipea.

The report states that substantial increases in public spending have provided only “limited” social benefits, citing growth in homicide statistics. Brazil registered 62,517 homicides in 2016, meaning the murder rate has crept over 30 per 100,000 for the first time ever, according to data released last week by the government’s economics institute, Ipea.

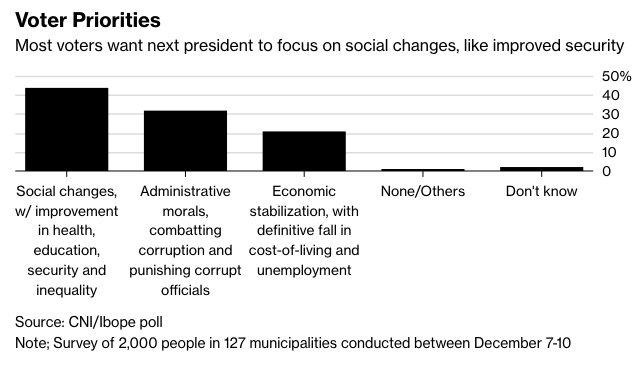

Nearly half of Brazilians surveyed late last year said that the next president’s priority should be improving security, health, education and inequality, according to a CNI/Ibope poll. That topped the roughly one-third of people who said the winning candidate should focus on fighting corruption, and was more than double the amount who said the main goal should be stabilizing the economy, fighting inflation and lowering unemployment.

Budget Limitations

Budget Limitations

Amid tepid recovery from Brazil’s two-year recession — the worst on record — there are limited funds available to address rampant criminality. With most Brazilian states constrained by the dire state of their fiscal accounts, it’s unlikely spending on public security can remain stable as a percentage of GDP going forward, the report said.

“In a context of budget limitations, it’s essential to base future public security policies on cost-benefit analyses, prioritizing those that bring the greatest social return for each real invested,” the report said. “Increasing public security policy efficiency depends on establishing evidence-based security policy.”

Evidence-Based

Evidence-Based

The report marks a departure from past plans, which have rarely advocated for data-driven or evidence-based policies, according to Robert Muggah, research director for security think tank Instituto Igarape, which provided data and technical inputs for the report. The economic cost of crime calculated for 2015 has likely risen considerably since, given the increase in the number of homicides, violent crime and property crime, he said in an email.

More specifically, the report recommends violent crime be the initial focus of scarce resources while avoiding investment in strategies that indiscriminately increase Brazil’s rising prison population, particularly for non-violent offenses. Brazil has the third-highest prison population in the world, of whom two-thirds are either in pre-trial detention or jailed on drug-related charges, Muggah said.

“The country urgently needs drug policy reform, alternative sentencing for non-violent offenses, and recidivism reduction — not more prisons,” he said.

— With assistance by Simone Preissler Iglesias