The End of Homicide: How to Halve Global Murders in a Decade

The world has never been safer than it is right now. Most forms of violence have dropped precipitously over the past few centuries. Although conflict deaths recently spiked (the war in Syria accounts for one third of all war-related killings today), fewer people are dying from warfare than at virtually any time in human history. Terrorist violence also increased over the past two years—especially in six countries the Middle East, Africa, and South Asia—but it still pales in comparison to rates in the 1960s and 1970s. Most impressive of all, homicidal violence is in steady retreat almost everywhere, especially the West.

The lethal violence that persists is unevenly concentrated. Almost half of the roughly 430,000 annual murders around the world are generated by just 25 countries. A handful of states in Latin America—Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Venezuela—account for one quarter of all homicides on the planet. As many as 47 of the 50 cities with the highest murder rates are located there. The region is also one of the only parts of the world where murder rates continue climbing. A few other giants, notably India, Nigeria, South Africa, and the United States, also register comparatively high absolute murder tolls, although for the most part, conditions there are improving.

The best way to ensure the continued downward trend of violent deaths is to concentrate reduction efforts in the world’s most badly affected countries and cities. Preventing and ending armed conflicts through early diplomacy and peace agreements is statistically correlated with saving lives. There is also evidence that investing resources in high-risk people and places can reduce violent crime at relatively low political and economic cost. The most successful measures typically combine hard commitments, valid and reliable data, realistic milestones and targets, and a laser-like focus on hot spots.

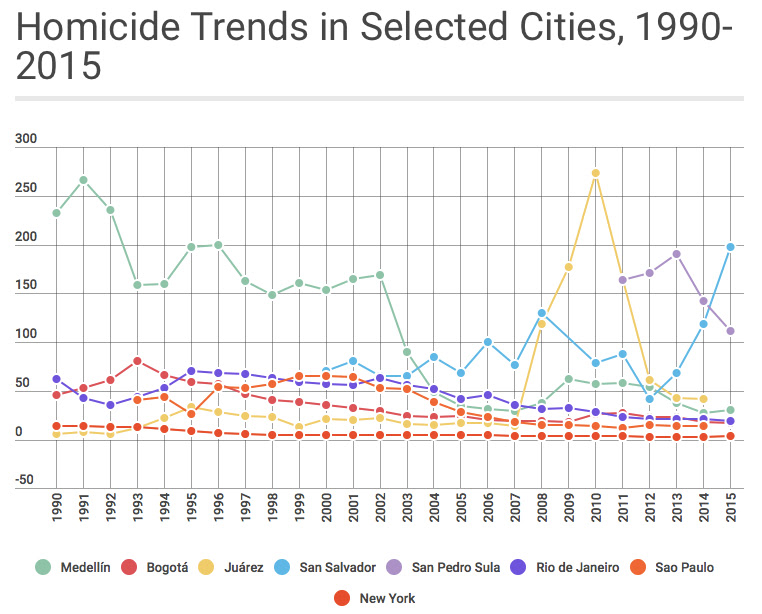

Some of the toughest places on earth have produced stunning turnarounds. Take the case of Bogotá, which between 1995 and 2013 saw its homicide rate plunge by 70 percent, from 80 to 20 murders per 100,000 inhabitants. Medellín, once the world’s most violent city, experienced an even more dramatic 85 percent reduction in murder between 2002 and 2014. The most impressive rebound in recent years has to be Mexico’s Ciudad Juárez, which saw the homicide rate tumble almost twentyfold from 282 per 100,000 in 2010 to 18 per 100,000 in 2015.

So what, statistically speaking, is required to cut homicide in half? Not as much as you might expect. For a country or city to reduce its homicide rate by 50 percent in a decade, it would have to clock in year-on-year reductions of roughly 7.1 percent. For example, in order to halve lethal violence in the world’s murder capital—San Salvador—the city would need to register 35 fewer murders than the previous year (for ten years). And to split El Salvador´s murder rate the country would need to register annual declines of at least 465 murders. El Salvador, it is worth nothing, is on track to achieve this goal in 2016. The tricky part is ensuring sustained reductions.

Dropping homicide by 50 percent is not just a thought experiment. Declines of this magnitude are achievable. There are plenty of examples of countries and cities, especially in North America and Western Europe, that dramatically reduced homicide by more than 7.1 percent per year. Take the case of the United States, which saw homicides fall nationwide from 9.4 per 100,000 in 1990 to 5.5 per 100,000 in 2010. And that’s not all: violent crime has fallen roughly 51 percent between 1991 (759 violent crimes per 100,000 people) and 2014 (387 violent crimes per 100,000 people).

Social scientists have struggled to account for the remarkable drop in violence across the United States and other parts of the world. Explanations vary, including improvements in policing, higher employment rates, changes in alcohol consumption, incarceration policy, legal abortion, and even the reduction of leaded gasoline. Other researchers point to long-term historical trends such as the civilizing process and deepening of the rule of law. Academics are having an equally hard time explaining the recent uptick in homicides in some U.S. cities from 2015–2016.

While overall strategies will vary from place to place, there are four basic steps for cutting homicidal violence.

First, investments in reducing murder must be data-driven, evidence-based, and problem-oriented. Incredibly, less than six percent of the security and justice measures implemented in Latin America and the Caribbean have come with any kind of monitoring system to judge their effectiveness. Too often, strategies to reduce lethal violence are not guided by good information regarding what works. The result is wastage and disappointment. Although not particularly sexy, the most successful measures are those that are guided by solid data and subjected to rigorous evaluation. For example, CompStat-style systems that combine crime mapping with intelligent police deployment are credited with a 13 percent decrease in homicide in the United States. Likewise, the former mayor of Cali, Colombia believes that real-time crime mapping contributed to a drop in homicides from 124 per 100,000 to 86 per 100,000 in just three years.

Second, scarce resources available for law enforcement and social services should be targeted at high-risk people, places, and behaviors. In many major cities around the world, more than half of all homicides occur near less than two percent of street addresses. A tiny number of people are responsible for (and are victimized by) a disproportionate amount of crime and violence. And in most cases, access to alcohol and firearms is strongly associated with the high prevalence of lethal violence. If preventing homicide is the goal, as it was with Boston’s Operation Ceasefire project and Chicago’s Cure Violence program, focusing on the riskiest areas and combining smart policing with social prevention including targeted support and job opportunities for at-risk youth will reap the most dramatic returns.

Third, sustained reductions in murder require strong social cohesion and what sociologists call collective efficacy—the ability of community members to control the behavior of others, especially in violence-prone neighborhoods. In other words, members of the community need to take an active part in creating safer spaces. Former Bogota Mayor Antanas Mockus replaced corrupt police with over 400 street mimes in a gesture meant to restore civility in the city. He also introduced open-air concerts, bars, and special nights designated for women. Social cohesion can also be incubated through intelligent urban design that improves the quality of interactions between residents. First-class public transport, high-quality schools, well-lit parks, and other neighborhood improvements are remarkable crime reduction tools. Subtle design adaptations that promote natural surveillance can be remarkably effective.

Finally, leadership is a cornerstone of any lasting homicide reduction effort. It is up to national and municipal authorities, the business community, non-profit organizations, and universities to take ownership of the problem. In most parts of the world, murder is still a taboo subject and reduction efforts are left to the police and criminal justice system to manage on their own. An index of the likely success of homicide reduction is that commitments are sustained over time by successive mayors. In Medellin, the city’s current mayor, Federico Gutiérrez, is determined to drive homicide down to 15 per 100,000 during his term by doubling down on reforms started by his predecessors, including Sergio Fajardo and Alonso Salazar over ten years ago. Another is that societies work not just to reduce murder rates, but also the underlying impunity that keeps violent crime intolerably high.

With these steps, the world can certainly become safer still.

By Robert Muggah and Ilona Szabó de Carvalho

Opinion editorial published in 7 September, 2016

Foreign Affairs