The apps that map violence – and keep Rio residents out of the crossfire

Rejecting official information channels, Rio’s citizens are navigating their city using crowdsourced data on shootings and robberies as they happen

05/04/2018

By Flávia Milhorance

Originally published on The Guardian

A red spot on the map means gunfire, so I avoid going there,” says Leonardo Duarte, who works on the streets for a rehabilitation clinic in Rio de Janeiro. Shootings and violence are routine in his neighbourhood of Vigário Geral, a slum in the grip of conflict between rival drug-trafficking gangs. To stay out of danger when navigating the city he has a strategy: never go anywhere without checking his phone for live crime data.

A red spot on the map means gunfire, so I avoid going there,” says Leonardo Duarte, who works on the streets for a rehabilitation clinic in Rio de Janeiro. Shootings and violence are routine in his neighbourhood of Vigário Geral, a slum in the grip of conflict between rival drug-trafficking gangs. To stay out of danger when navigating the city he has a strategy: never go anywhere without checking his phone for live crime data.

An increasing number of Rio residents are subscribing to crowdsourcing apps and following the social network pages of crime-watch groups such as Basta de Violência (No More Violence) and Realidade do Rio de Janeiro (Reality of Rio de Janeiro).

These new sources of real-time information are shaping how many residents navigate the rising day-to-day violence in the city – which is currently the subject of a controversial military security intervention. Duarte updates the groups if he comes across a violent episode. “I send out information when I see or hear something,” he says.

Duarte’s daily decisions are based mainly on the mobile app Onde Tem Tiroteio(OTT, or Where the Shootouts Are), which sends out alerts for incidents across Rio de Janeiro state. Set up in 2016 by four friends, OTT tracks gun and gang violence based on residents’ reports. It has grown fast.

Co-founder Dennis Coli explains that he and his friends take turns managing the operation, which receives 80 to 100 alerts every day from a network of 1 million people. They include subscribers to the app and followers on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, WhatsApp and Telegram.

OTT eschews official statistics. Instead, it crowdsources data on shootings and arrastões (organised gang looting) and checks these anonymous reports with a core WhatsApp network of 2,000 people who OTT considers reliable. Only 10% of the original crowdsourced reports reach the public. “We don’t want to spawn unnecessary chaos,” says Coli.

The four founders had all experienced violence before starting the self-financed voluntary project. In 2015, Coli had a gun pointed at him when he unwittingly stopped his car in a spot used by drug dealers.

Two years after releasing the app, he admits feeling even more frightened, but says the app’s database means he can avoid problem areas. “I anticipate,” he says. “For example, I never drive on highways such as Linha Vermelha, Dutra and Brasil on Sunday afternoons. There is always an incident.”

The Fogo Cruzado (Crossfire) app, set up by Amnesty International and now managed by the Update Institute, is similar. It cross-checks reports from a range of sources – including journalists, police officers and residents – across Greater Rio de Janeiro. It also trawls official police and press data. It reports an average of 16 shootouts a day across Greater Rio, compared with OTT’s 14 across Rio state.

“These [incidents] were happening already,” says Crossfire co-founder and journalist Cecília Olliveira, who designed the app after failing to find statistics on stray bullets for a story. “The difference is that we count them now. I’m quite sure they are still underreported.”

Last month Olliveira posted on Fogo Cruzado about gunshots close by Praça da Bandeira. Later she realised they were the shots that killed the Rio city councillor Marielle Franco, whose murder led thousands of outraged Brazilians to protest on the streets. Olliveira knew her personally. “This is the third time a gunshot I posted about hit someone I know,” she says. “Two of them have died.”

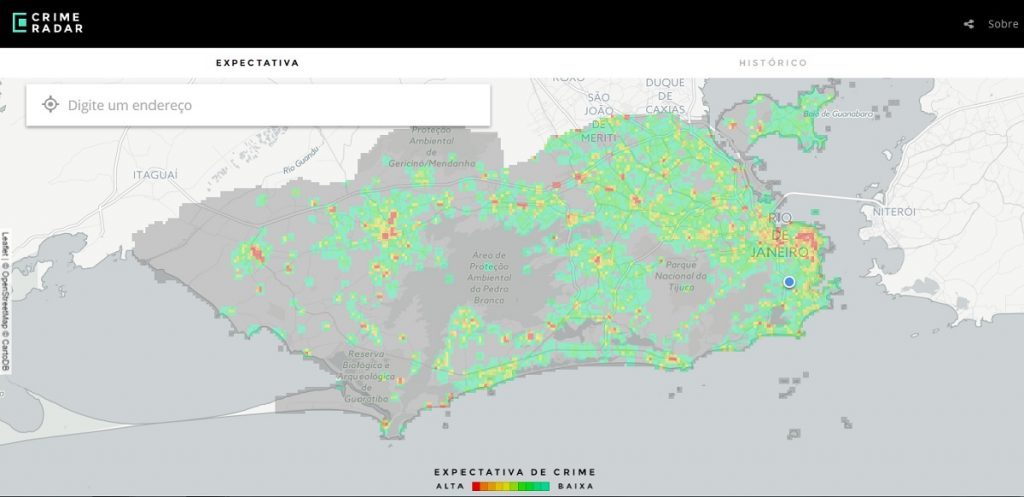

Robert Muggah, research director of the Igarapé Institute thinktank, says Fogo Cruzado and OTT fill knowledge gaps and redirect the discussion of crime away from distant trends and toward its immediate impacts. Igarapé’s own app, CrimeRadar, uses artificial intelligence to analyse 14m official crime reports from the past five years and predict crime patterns across the city.

But Muggah cautions that Facebook crime-watch groups can be “exceedingly conservative”, often calling for severe sentencing legislation and featuring “racist and pejorative” headlines and text. “They have certainly expanded the spread of fake news,” he adds.

Rio’s military police would rather residents consulted their official Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and YouTube accounts. “There is a lot of misinformation circulating on the internet,” says its press office.

But for many, the immediacy of the apps wins out. As Jaciara da Conceição looks at her smartphone, audio alerts and images from WhatsApp pop up on her screen. She hates seeing the graphic photographs of young men’s mutilated bodies, “but it is difficult to avoid getting them”, she says.

When a drug-related conflict broke out in her Greater Rio neighbourhood of Parque Paulista a few months ago, four public buses were set on fire. She saw the flames of one from her window, and heard about the others on a Facebook page.

Conceição says she was sceptical when she heard that a drug dealer was advising people to avoid the streets, but the following day the shootings restarted: “So it was true.”