Egypt´s terrorist violence is a reminder of the new normal

November, 2017

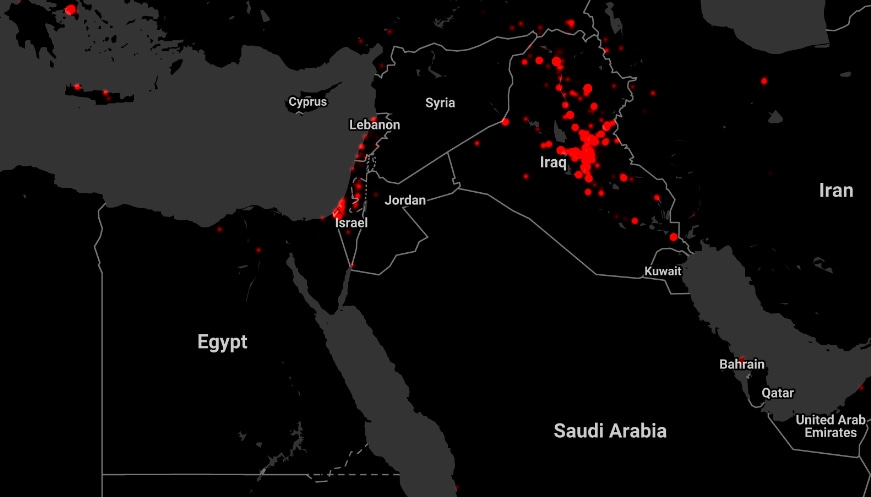

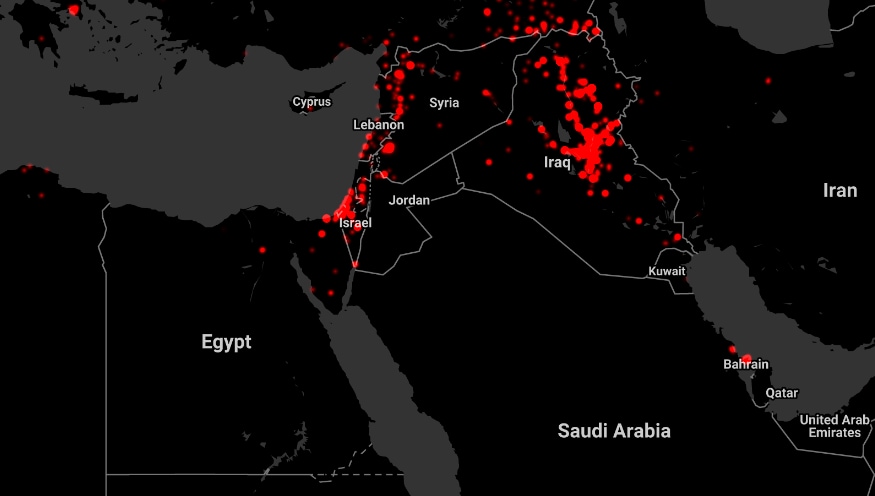

Friday´s savage attack in Egypt is a reminder that the vast majority of terrorist-related killings occur in less well known cities far from the media glare. To be sure, the brutal murder of 305 practicing Sufis in Bir al-Abed represents a dangerous escalation in the Sinai. It is also a symptom of the dramatic expansion of terrorism across North Africa and the Middle East over the past decade.

A recent study of more than 1,300 cities shows that Egyptian cities, alongside other Afghan, Iraqi, Libyan, Nigerian, Pakistani, Somali and Syrian urban centers, register considerably higher levels of terrorist violence than their counterparts in the United Kingdom, France, Germany or the U.S. Cities like Baghdad, Mogadishu, Karachi, and Kabul have experienced tens of thousands of killings since 2006.

Egypt has experienced a sharp increase in extremist violence, especially since an Islamist insurgency flared-up over the past few years. The vast majority of the estimated 2,976 documented terrorist events in Egypt since 1970 occurred after 2013. According to the Global Terrorism Database, some 315 people were killed in 2013 compared to 49 in 2012. Another 582 people were killed in 2015. And the numbers will likely surge higher still in 2017, especially since the Egyptian authorities have vowed to crack down on the Sinai.

The rising tide of terrorism

2010

The grim truth is that the only future scenario we can predict with certainty is that there will be more terrorist attacks. The most effective way to begin reducing them would be to dramatically scale-up efforts to end simmering armed conflicts across the region. Given rising geopolitical tensions, this is unlikely in the short-term. And while terrorist violence will never be entirely prevented, there are several strategies that can limit its effects.

It is first important to recognize that terrorist groups routinely target “soft” targets in cities and towns, especially where people are most likely to gather. The latest attack on the al-Rawda mosque is no exception. Indeed, cities and their populations are the target, not collateral damage. Extremist groups such as Al Qaeda, Al Shabaab, Boko Haram and Islamic State are expert at separating different population groups from one another. By bombing religious sites, street markets, sports stadiums, theaters and police stations, they force people indoors in what amounts to physical and psychological siege.

More and more cities are designing-in resilience to counteract urban terrorism. The most common procedures involve improving intelligence cooperation, deploying extra layers of police surveillance in crowded spaces and investing in smarter police-community relations. Other strategies involve reshaping the city landscape, including unobtrusive physical barriers around tourist sites, government offices and major businesses.

The challenge is: how to minimize the risk of terrorism without choking city life altogether?

If cities are going to get to grips with these threats, they also need to think further ahead. For example, mayors and police chiefs may need to start normalizing the threat, investing in both prevention and consequence management. Businesses must regularly update their continuity plans and governments must improve their inter-agency communications to separate the signal from the noise. An inescapable conclusion is that city dwellers around the world will need to get used to the new normal.