Dining With Madonna No More, Rio Grapples With Rising Crime

Published originally in Bloomberg | by R.T. Watson | August 18. 2017

In Rio de Janeiro’s bohemian neighborhood of Santa Teresa, the rain-forest chic Aprazivel restaurant is nearly empty on what should be a busy Saturday night.

Celebrities including Madonna and Tom Cruise have enjoyed the stunning views and tropical dishes at the landmark Rio eatery. But these days even natives are reluctant to risk driving after dark to the hilltop spot because the surrounding area has seen a spike in violent crime, said co-owner Pedro Hermeto.

“Drivers try to convince people not to go, saying it’s very dangerous, that it’s a risk zone and there are a lot of murders,” Hermeto said.

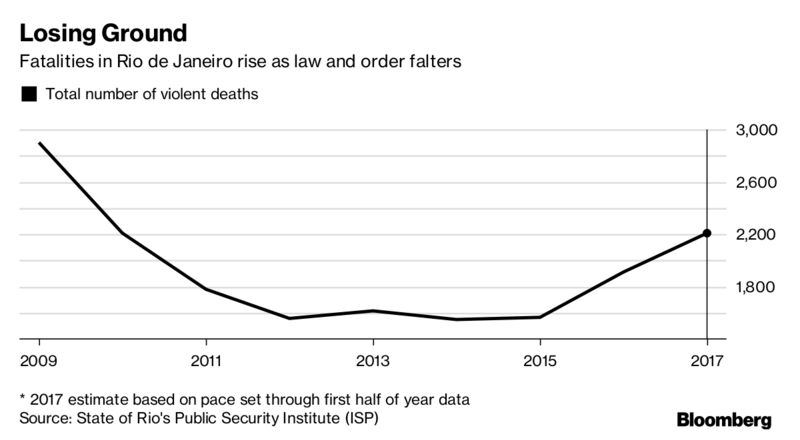

Rio invested heavily ahead of hosting the World Cup and Olympics to expand policing and bring law and order to its infamous slums — including those wrapped around the cascading slopes of Santa Teresa. For a while the initiatives paid off.

But the hard-won gains are unraveling as Brazil succumbs to the boom-bust cycle it has been famous for since the colonial period. Rio’s situation is more dramatic as its oil industry, a main source of revenue and jobs, imploded amid lower crude prices and a corruption scandal. Unemployment in the city more than doubled to 15.3 percent since Brazil sank into recession. Local security forces have suffered attrition and delayed salary payments.

Elusive Recovery

Rio desperately needs a foothold to mount a recovery, but it’s running out of options as rising crime scares tourists and drives up the cost of business for everyone from supermarkets to utilities like Light SA that suffer from growing power theft.

Armed bandits robbed a mobile phone store on Friday at a mall right across the bay from top tourist destination Sugar Loaf mountain. Police chased the thieves through the shopping center, startling patrons and prompting some shops to close even though nobody was hurt, according to local media reports.

“You have companies now that are taking a lot of care evaluating whether or not to continue doing business in the city, given that the uncertainty is huge,” Marcelo Haddad, the head of the Rio Negocios investment promotion agency, said in a telephone interview. “There has been a significant reduction in the enforcement capacity of Rio de Janeiro’s police.”

The challenges faced by Aprazivel, which has suffered as much as a 40 percent drop in revenue and had to lay off 35 employees in the past year, are common. Violence cost Rio about $100 million in lost revenue during the first four months of the year, according to Brazil’s National Confederation of Commerce of Goods, Services and Tourism. Local tourism leaders sent an open letter to President Michel Temer in May pleading for help with security.

The city’s main roadways have become more dangerous for consumers and businesses with more than 28 cargo thefts each day in the state, according to local newspaper O Globo. That is increasing the price consumers pay for medicines and electronics by up to 35 percent, said the Firjan industry association. Supermarkets are also expecting retail prices of some goods to rise as much as 20 percent due to crime-related transport costs, according to the supermarket association Asserj.

Just a Tourniquet

The highway robberies and other security concerns prompted Temer to deploy about 8,500 national guard troops in Rio this month. So far the results are hard to see. It is still too dangerous to deliver merchandise to many formal businesses, and stolen goods continue to be sold at informal markets at cut-rate prices by merchants who pay no taxes.

Temer’s initiative is nothing more than a “tourniquet” unable to address the structural issues behind the deterioration in public safety, said Institutional Security Minister Sergio Etchegoyen. Part of the problem is the amount of attrition at state and city law enforcement in recent years, with civil and military units losing about 3,000 officers since 2012. The state’s multibillion-dollar budget deficit hampers its ability rebuild security forces anytime soon.

“The fact that everyone agrees on is that the security situation has deteriorated considerably since late 2016 and into 2017,” Robert Muggah, a research director at the Rio-based think-tank Instituto Igarape, said by email. “The short- to medium-term prognosis is not good.”

In a provocation to security forces, criminals hung a machine gun over the shoulders of a Michael Jackson statue at the city’s first pacified slum, where he once filmed a music video highlighting social injustice. The machine gun episode was featured prominently by daily newspaper Extra, which days later started a new ‘War’ section to chronicle the surging crime wave.

For Aprazivel’s Hermeto, who heads an association made up of local businesses belonging to Santa Teresa, survival means taking matters into his own hands. The association he heads will pay for and install as many as 40 security cameras in the area and hire someone to monitor them. The hope is to curb criminal activity and help rescue the neighborhood’s reputation before it’s too late.

“We know that the state doesn’t have any money to invest,” Hermeto said.