Caught between police and gangs, Rio de Janeiro residents are dying in the line of fire

Publicado originalmente por Robert Muggah em The Conversation, em 04/09/02017

In Rio de Janeiro, where murder rates this year have soared to their highest levels in a decade, violence stalks even the youngest residents.

In July an unborn child was struck by a stray bullet, which severely damaged his spine and perforated his lungs. Doctors saved his mother, Claudinia Santos, but little Arthur did not make it.

His killing sparked outrage, laying bare a terrifying danger facing Rio’s citizens: death by crossfire. That’s what happens when gun battles between heavily armed police, drug trafficking groups and militias rage in a city’s streets.

In 2016, more than 5,000 people were murdered in Rio, among them scores of people killed by stray bullets.

War on the poor

According to a snapshot of 2017 civil police data, so-called “stray bullet incidents” are most frequent in Rio’s poor north and west zones, home to many favela neighbourhoods.

At the time of Arthur´s murder, authorities in Rio had already reported at least 632 unintentional gun-related killings and injuries in 2017. The majority of the victims lived in socially marginalised areas, and consisted chiefly of women, children and older people.

This demographic profile reflects similar trends uncovered in epidemiological studies conducted in both the United States and Colombia, where data on stray bullet incidents has also shown that most victims tend to be young, old or female.

This profile diverges notably from that of the typical perpetrator, who in both Rio and the US are predominantly men 15 to 29 years old.

In other words, those caught in the crossfire have nothing to do with the events that generated it; they are, in the most literal sense, innocent bystanders.

A brief history of violence

Stray bullets are not a new problem in Rio. When crime rates peaked here some two decades ago, hundreds more people were unintentionally shot each year.

In the mid-1990s, one former mayor memorably described the bullet-riddled city as a “tropical Bosnia” and hinted that an undeclared war was underway. Back then, fearful residents commonly reinforced their windows and walls with steel plates and concrete.

Starting about five years ago, violence in Rio began to ease somewhat. As the city’s controversial Police Pacification Units, or UPPs, reclaimed some of city’s favelas from gangs, they helped murder rates decrease by 65% between 2009 and 2012.

But the reforms at the heart of the UPPs – neighbourhood occupations, proximity policing and use of non-lethal force – began to deteriorate after the 2016 Rio Olympics, and crime is once again spiking in Rio’s favelas.

Rio de Janeiro residents killed or injured by stray bullets every two days – 95% of those in favelas #Brazil https://t.co/Y3zCD4RvrP

— Shasta Darlington (@ShastaReports) May 16, 2017

Crossfire deaths are just one consequence. These communities suffer acutely from all forms of violence, including police brutality, which has been growing in frequency and severity since the UPP’s collapse.

I believe that’s because organised crime, stray bullets and aggressive policing are mutually reinforcing. Pitting police against gangs in an overt turf war has spawned a mini arms race, with all sides – from drug dealers to beat officers – resorting to ever-higher calibre weaponry.

With the recent arrival of 8,500 soldiers to go after gangs and illegal weapons in Rio de Janeiro, the twelfth military deployment there since the early 1990s, the violence could escalate further still. Brazil’s minister of defence has described the armed forces as an “anaesthetic” for the city.

On July 2 2017, the Rio de Janeiro state civil police announced that 632 people had died in crossfire this year. On average, then, the official statistic is that a Rio resident is hit by a stray bullet every seven hours.

Caught in the fogo cruzado

The actual number is likely considerably higher.

Most law enforcement and public health specialists limit the application of the term to instances when a bullet escapes the immediate scene of a shooting and results in a fatal or non-fatal injury. This narrow definition leaves out the many instances where shots are fired but no casualties are reported.

In 2015, the local newspaper Extra challenged the way the city’s Institute for Public Safety (ISP) counted stray bullets, accusing officials of dramatically under-reporting. Applying the government’s categorisation scheme, reporters found just 160 stray bullet incidents between January and June 2014, leaving another reported 39 crossfire deaths and 194 stray bullet injuries uncounted.

The ISP has now partnered with local academics and the Rio de Janeiro state civil police to refine how it registers these incidents, but commentators disagree on whether the new definition is any better.

The media, too, under-reports on stray bullet incidents. According to a 2016 United Nations-sponsored study that tracked the “stray bullet incidents” documented in news outlets across Latin America, Brazil ranked first for crossfire-related injuries and deaths in 2014 and 2015, with 197 incidents (98 deaths and 115 injuries).

It was followed by Mexico (116 cases) and Colombia (101 cases). In all three homicide-beset nations, this is surely a low estimate.

To fill these information gaps, activists in Rio de Janeiro have developed apps. Amnesty Brazil’s Fogo Cruzado (Crossfire) has reported more than 2,000 shooting in the last 120 days, an average of 16 a day.

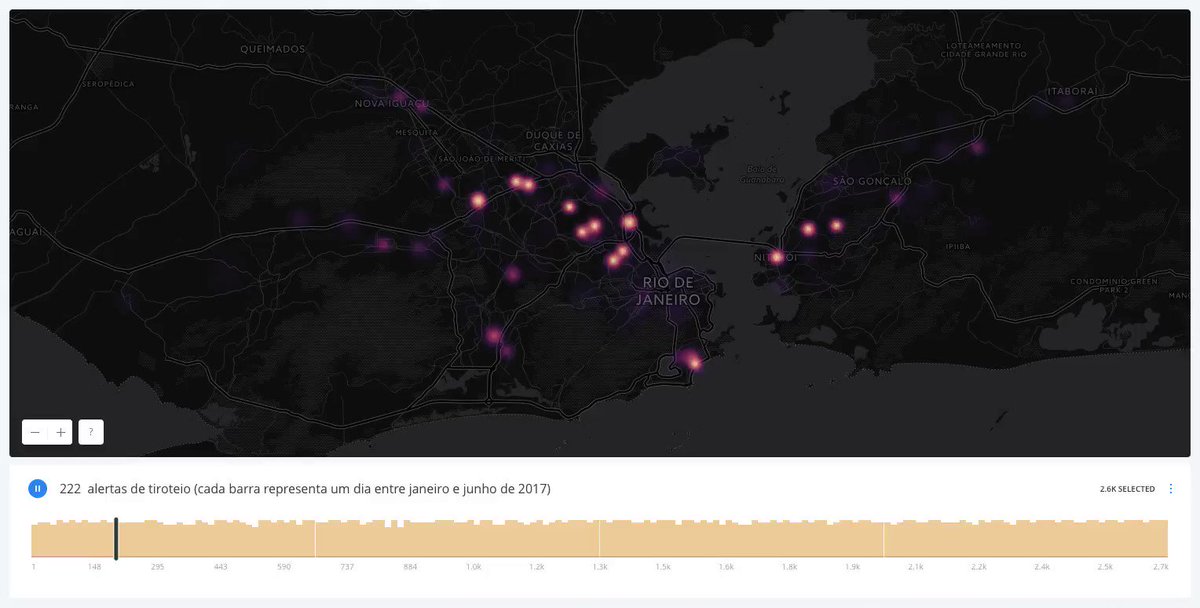

Press play below to see all reported shots fired in Rio from January through June 2017:

But crowd-sourcing platforms have their weaknesses, too. They rely on citizens to file reports online, meaning better coverage in more tech-savvy neighbourhoods. They also capture all incidents, both verified and unverified.

Don’t shoot

Ambiguous defitions and under-counting mean that violence analysts like me don’t actually know whether crossfire killings are on the rise.

But we do know this: Rio’s stray bullets are no accident – they’re the predictable outcome of a public security policy that privileges aggressive policing over prevention. Too often police in Rio are trained to shoot first and (maybe) ask questions later. When threatened, officers routinely fire off a disproportionate number of rounds – often at close range.

And when trigger-happy cops wield powerful assault rifles, as Rio’s do, they can kill or injure people up to three kilometres away.

Drug trafficking factions do precisely the same thing, with predictably deadly outcomes for bystanders.

Limiting confrontations in dense urban areas, including through super-targeted “hot spot” policing, could dramatically reduce the gun battles that end up claiming innocent lives.

Such reforms would require better police training and more oversight of errant officers, though, something that Rio’s underfunded and overstressed police force cannot do without able leadership and additional resources.

There are several other ways to limit stray bullet incidents: passing and enforcing stricter gun regulations, stemming the leakage of illegal weapons onto the street from public and private security forces, marking and tracking police bullets – even just advising people against firing celebratory shots in the air.

In the absence of such emergency measures, favela residents will have to keep dodging bullets while the rest of us look on in horror.