Brazil’s Cybercrime Problem

Time to Get Tough

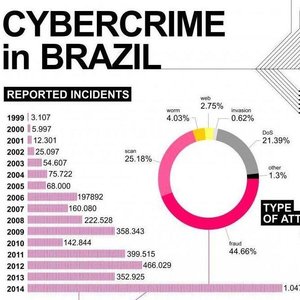

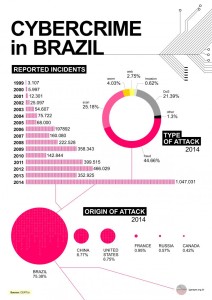

Brazil is at the epicenter of a global cybercrime wave. The country ranks second worldwide in online banking fraud and financial malware, and the problem is only getting worse. According to official sources, the number of cyberattacks within the country grew by 197 percent in 2014, and online banking fraud spiked by 40 percent this past year.

Yet much of the Brazilian public remains unaware of the scale of the problem. Policymakers are beginning to respond to the threat, but only in a piecemeal way. If Brazil is to successfully combat cybercrime, a much broader public discussion is required. Legislators, law enforcement agencies, businesses, civil society organizations, and private citizens all need to take cybersecurity much more seriously.

EASY PICKINGS

The cost of cybercrime to the Brazilian economy is unclear. One report claims that data theft in Brazil accounted for $4.1 billion to $4.7 billion in losses in 2013. According to other sources, the equivalent of about $3.75 billion has been hacked from the Boleto Bancário, a payment method managed by the Brazilian Federation of Banks, since 2012 alone. This amounts to roughly 495,000 transactions involving 30 banks and affecting more than 192,000 victims. There is almost no publicly available data about which banks are affected.

Most of what we know comes from surveys of businesses and users. A recent study of 450 São Paulo businesses determined that small- and medium-sized businesses are most at risk. Hackers use basic phishing strategies, typically sending e-mails to obtain sensitive information such as passwords and credit card details, and company employees often unwittingly download malware. Some of these vulnerabilities are easily mitigated, including by requiring employees to periodically reset passwords and avoid downloading suspicious messages.

The fact that so many Brazilians are victims of cybercrime is not entirely surprising. After all, 58 percent of the country’s 200 million citizens are connected to the Internet. This compares with 49 percent for both China and South Africa and 18 percent of Indians. At least 45 percent of all banking transactions in Brazil are digital. Brazil, with 130 machines per 100,000 adults, has a greater density of ATMs than the United Kingdom (127 per 100,000), France (109 per 100,000), or Germany (116 per 100,000), according to World Bank data.

And legislation to prosecute cybercrime is weak. Approved in 2012, the so-called Carolina Dieckmann Law established hacking as a criminal offense. But would-be cybercriminals may not find the law’s weak penalties (just three months to one year in prison and a fine) to be much of a deterrent. The U.S. Personal Data Privacy and Security Act, by comparison, comes with sentences of up to five years and/or a fine for similar crimes. Also in the United States, the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, a law protecting federal computers and banking systems, imposes penalties of up to ten years in prison (with up to 20 years for the second and subsequent offenses) along with hefty fines (up to $250,000 for individuals and $500,000 for organizations). The European Union also recently stepped up sentencing guidelines for the hacking of personal data and other cyberattacks that impact critical infrastructure.

Brazil’s policing capacity is also limited. Law enforcement officials lack the resources to crack down on these types of cybercrimes, and although Brazil’s Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation and Ministry of Defense are trying to stimulate more private sector involvement in cybersecurity, their efforts are taking time.

A MUCH-NEEDED DISCUSSION

Given the scale of Brazil’s problem with cybercrime, it is surprising how little is known about it. The silence is partly intentional. Large banking and retail corporations prefer to keep quiet about the extent of their losses for fear of damaging their reputations and scaring clients. Although a recent International Telecommunication Union report ranked the country fifth on its Global Cybersecurity Index, which scores countries on national cyber-awareness, most citizens remain unaware of how vulnerable they are to cybercriminals.

Yet public awareness may be growing. Several high-profile incidents are alerting Brazilians to the gravity of online threats. For example, Ana Paula Araújo, a journalist and host of the popular Bom Dia Brasil television program, was reportedly the victim of a hacker who successfully stole 30,000 reais (about $8,000) from her bank account in mid-July.

Meanwhile, a group of Brazilian public and private sector groups are advocating for greater Internet governance and Net neutrality. This is the principle that Internet service providers and governments should treat all data on the Internet equally and is intended to preserve the right to communicate freely online. The groups have helped develop an Internet bill of rights, the so-called Marco Civil da Internet, which was approved by the country’s National Congress in 2014. The bill of rights puts the onus on software developers and telecommunications companies to include safeguards (including encryption) in their products and services. It holds companies liable for privacy violations.

Some Brazilian companies and government agencies are also taking action. They are turning to foreign technology and expertise to protect their data networks and servers. The Brazilian government purchased Russian software, for example, to protect the networks of Brazilian state company Sanepar, the agency charged with managing water supply and sanitation in the Brazilian state of Paraná. The agreement was signed during a visit by Russian President Vladimir Putin to Brazil in 2014 and involves real-time fingerprint identification for around ten million people. The federal government is also looking abroad for the acquisition and use of surveillance tools of its own.

For example, Brazil’s Federal Police Department recruited Italian surveillance malware vendor Hacking Team, which sells its spyware to government agencies such as the FBI and U.S. Army, as well as to clients throughout the Middle East and Africa. WikiLeaks recently published a slew of e-mails detailing how the company sells technology to governments, enabling them to manipulate computers and cell phones and employ additional methods of unmasking personal data or tracking individuals’ habits. And although companies such as Hacking Team tout their products’ legitimacy as an important law enforcement tool, there is also evidence that governments use such technology to monitor those critical of government policies, including journalists and human rights advocates.

There is much talk of beefing up cybersecurity efforts in Brazil during the 2016 Olympics as well. The Centro de Defesa Cibernética do Exército Brasileiro announced in June that it would be contracting 200 cybersecurity specialists, technicians, and military personnel in an effort to protect public and private sites during this period. Although this is critical, a much more urgent discussion is required with the wider Brazilian public.

Brazil needs to face up to its cyber-vulnerabilities. This requires a more honest and public conversation about the dimensions of the online threat and the importance of digital hygiene. At a minimum, Brazilians need to take more precautions to protect their mobile devices and reduce social network risks. Banking and other financial institutions need to be more transparent about how they are responding to cybercrime and protecting client data. And the government has to ensure that national legislation to prevent and fight cybercrime is keeping pace with the speed of technological developments. In spite of the promise of the new Marco Civil da Internet, current laws are woefully inadequate for the threat. Brazil needs a national road map for cybersecurity and should establish an official agency to direct the country’s strategy. It’s time for Brazilian lawmakers to get serious about cybercrime.

Nathan Thompson and Robert Muggah, Foreign Affairs