Executive Summary

Conflict prevention has a long history within the context of the international peace and security architecture. In recent years, there has been a push to vitalize the idea. The new UN Secretary General has called for the restoration of conflict prevention to the center of the organization´s agenda. The Secretary General and others see conflict prevention as not only central to the UN´s mandate, but also as a growing responsibility for the African Union (AU), other Regional Economic Communities (RECs), and Regional Mechanisms (RMs). The growing focus on “Sustaining Peace” has shown that the senior leadership of most multilateral organizations are committed to expanding political commitment, resources, and innovative thinking to produce more effective approaches to the prevention of the outbreak or recurrence of conflict and violence.

A critical question concerns “what works” when it comes to preventing conflict. There is growing interest by a wide range of multilateral and bilateral agencies in identifying innovations in conflict prevention—new and tested approaches, practices, and tools that increase the effectiveness and efficiency of prevention. The idea that a thousand flowers should bloom is no longer tenable. Curiously, one of the central challenges in identifying and developing preventive solutions relates to the lack of conceptual clarity about what conflict prevention actually means. There are broad and narrow interpretations—all of which make it difficult to move from theory to practice. Without an agreed typology of conflict prevention, it is difficult to prioritize, assess and evaluate competing policies, programs and projects on the ground. Indeed, despite a multitude of preventive initiatives underway around the world, we know little about what works, and why.

At the same time, conflict prevention is politically sensitive. Some member states of the UN and AU fear that the idea of conflict prevention intentionally or unintentionally reinforces security priorities at the expense of core human rights and development work – in other words, that it tends to securitize those organizations’ approaches. Others worry that conflict prevention infringes on state sovereignty and, taken to extremes, could be used as justification for heavy-handed interventionism. Still more believe that conflict prevention is too narrowly associated with the idea of state fragility, and that, as a result, related efforts have focused on low-income and conflict-affected states with insufficient engagement with the many transnational factors that drive armed conflict. What is more, some governments are concerned that the label of “conflict prevention” can generate stigmas and negative reputation effects for those countries that have become the focus of preventive efforts.

In order to clarify the concept of conflict prevention and provide a solid starting point for evidence-based analysis and response design, this handbook offers several key take-away points:

- Although the international community has focused heavily on the immediate side of conflict prevention, using tools such as mediation and good offices to prevent the imminent breakout or intensification of conflict, more attention is needed to structural prevention, with a longer-term view and corresponding policy approaches.

- Despite the heavy focus on individual states, conflict prevention requires greater attention to transnational factors, whether at the regional or global level. From arms flows to migratory fluxes and geopolitical meddling, transnational factors demand far more innovative international cooperation on conflict prevention.

- Given the evidence on how inclusive processes contribute towards positive peace, all types of conflict prevention responses – primarily whether immediate, structural or transnational – should incorporate the perspective, and attend to the needs, of population groups that are particularly vulnerable in conflict-affected contexts, including women, children, the elderly, and ethnic or religious minorities.

- Although global and regional epistemic communities have emerged around specific categories of conflict prevention, e.g. mediation and peacebuilding, promoting interaction and exchanges among those sub-groups is necessary for a more comprehensive approach to conflict prevention.

- There is urgent need for reliable data and analysis of conflict prevention that goes beyond case studies and draws on a wide gamut of methodologies, both qualitative and quantitative, combining them with innovative technologies that allow for data interactivity and visualization.

- Knowledge-building and policymaking on conflict prevention should not remain the exclusive or primary province of global powers and associated institutions. The international community should work to boost the role and even protagonism of Global South institutions in generating innovative solutions to conflict prevention based on localized knowledge and collaborative ties among institutions across the developing world.

This handbook seeks to build more clarity to conflict prevention concepts and practice. Based on extensive consultation and with support from Global Affairs (Canada), it offers a working definition and a typology of innovative preventive approaches. In setting out a standard nomenclature, the goal is to help improve knowledge sharing across Africa in particular. At the same time, the handbook is intended to provide policy makers and practitioners with insights and ideas for prioritizing, designing, implementing and evaluating conflict prevention. More specifically, the Handbook is designed to:

(a) give policymakers and practitioners in multilateral organizations, bilateral development and cooperation agencies, and stakeholders at the national and subnational level an improved understanding of the key conceptual dimensions of conflict prevention;

(b) provide a succinct typology of the principle conflict prevention practices;

(c) set out ways that gender can be operationalized in conflict prevention; and (d) offer concrete examples of innovative practice.

A particular effort was made to ensure that the handbook highlights concrete examples of innovative solutions. All of these are available on the Igarapé Institute´s website via the Innovation in Conflict Prevention initiative.

Introduction

After a half century-long decline, the incidence and severity of armed conflicts started increasing again in 2010. Data from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) shows that the number of non-international armed conflicts more than doubled since the turn of the millennium, and that there are now more armed groups involved. The Institute fir Economics & Peace (GPI) found that, in 92 countries, the level of peacefulness fell in 2017, while there were improvements in only 71 countries—a trend of declining peace that has continued for four years[i]. The Middle East and North Africa accounted for the majority of conflicts, but spillover effects into other areas, including sub-Saharan Africa, have also contributed to the deterioration in global peace.

The number of state-based conflicts have increased in Africa; in 2017, the continent experienced 18 such conflicts. A PRIO study notes that, while this represents a decrease from the record of 21 such conflicts in 2016, it remains substantially higher than ten years prior, with 12 such conflicts in 2007. The number of battle deaths has oscillated across the years, and in 2017 most occurred in Nigeria, Somalia and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The scenario for non-state conflicts is far more pessimistic. In 2017, Africa experienced 50 non-state conflicts, compared to 14 in 2011. This makes Africa by far the continent with the highest number of non-state conflicts. In addition, the number of battle deaths in African non-state conflicts has doubled during the same period, reaching 4,300 in 2017. These deaths have concentrated in the 11 African countries that saw non-state conflicts[ii].

These trends have translated into increased danger for civilians[iii]. In 2018, there were 68.5 million forcibly displaced people worldwide, including 25.4 million refugees and 10 million stateless people[iv]. OCHA estimates that more than 134 million people across the world need humanitarian assistance and protection, and that conflict remains the main driver of these rising humanitarian needs[v]. At the same time, the global humanitarian crisis takes place in a context of dwindling resources, not only for humanitarian response, but also for preventive initiatives, as multilateral organizations and donors undergo budget cuts. In December 2017, UN Secretary-General António Guterres spoke of a $11 billion gap in global humanitarian funding. Noting the likelihood of protracted conflict and the intensifying impacts of climate change, he added that there is no sign of a let-up in humanitarian needs[vi].

States seem to be channeling resources elsewhere, particularly towards military spending. Indeed, the increase on global conflict coincides with a sharp rise in global defense spending. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), total defense expenditure globally reached $1.74 trillion in 2017, a new record when adjusted for inflation. This amounts to 2.2 percent of global domestic product (GDP) or $230 per person[vii].

Wars are not just more common than in the recent past, they are more protracted and violent. Protracted armed conflicts—characterized by their longevity, intractability and mutability—are becoming more common not only due to the lack of respect for international humanitarian law, but also because the root causes of conflict are not being properly addressed. In many countries, armed conflict has become the norm rather than the exception. In addition, protracted armed conflicts with regional spillovers are not only provoking humanitarian disasters, they are also casting into doubt the international community’s mainstream approaches to dealing with conflict.

At the same time, international agencies committed to advancing peace, security, and development have launched new attempts to develop more effective ways of promoting peace and stability. During the first year of Guterres’ mandate, a joint effort by the UN and the World Bank resulted in a report titled Pathways for Peace: Inclusive Approaches to Preventing Violent Conflict. The report, launched in September 2017, marks the first substantial partnership between these two institutions—both originally created with the express mandate of preventing conflict—on promoting concrete ways of avoiding the outbreak or recurrence of armed conflict[viii]. As part of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) Network on Conflict and Fragility, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has developed new tools to evaluate conflict prevention and peacebuilding[ix]. Clearly, the level of interest in evidence-based research on conflict prevention has increased.

This handbook seeks to build more clarity to conflict prevention concepts and practice. Based on extensive consultations at the UN and the AU and with support from Global Affairs (Canada), it offers a working definition and a typology of innovative preventive approaches. In setting out a standard nomenclature, the goal is to help improve knowledge sharing across Africa in particular. At the same time, the handbook is designed to provide policy makers and practitioners with insights and ideas for prioritizing, designing, implementing and evaluating conflict prevention. More specifically, the Handbook is designed to:

(a) give policymakers and practitioners in multilateral organizations, bilateral development and cooperation agencies, and stakeholders at the national and subnational level an improved understanding of the key conceptual dimensions of conflict prevention;

(b) provide a succinct typology of the principle conflict prevention practices;

(c) set out ways that gender can be operationalized in conflict prevention; and (d) offer concrete examples of innovative practice.

The handbook is divided into three broad sections. The first part provides a succinct overview of the key debates and concepts related to conflict prevention, including as they have developed within the UN and the AU/RECs. Next, we define what is meant by innovation in conflict prevention. The third part of the handbook is devoted to a typology of conflict prevention that can be used to map and analyze conflict prevention practices and responses. The final part of the handbook includes a list of bibliographical references and related resources.

The handbook is part of a broader initiative, led by Igarapé Institute in partnership with the Institute of Security Studies (ISS), which aims to map, analyze, and promote innovative practices on conflict prevention in three regions of Africa: the Horn, the Greater Sahel, and the Great Lakes. The project, titled Innovation in Conflict Prevention (ICP), combines desk review and interviews with key stakeholders at the UN, AU, and RECs with fieldwork carried out between 2017 and 2018 in six African cases: Guinea-Bissau, Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, Somalia, and Mali. The initiative is also based on extensive interaction with relevant stakeholders at international organizations, namely the UN, AU, and RECs headquarters and field offices. Project outputs include a variety of policy briefs, research papers, op-eds, podcasts, and other publications, as well as a series of workshops held in Addis Ababa, New York, and Ottawa. The ICP initiative also yielded two technology-based components: a database of conflict prevention initiatives based on the typology in the handbook, and an interactive app, called CPeace (Connecting Peace), designed to promote interactivity among different clusters of conflict prevention practitioners, policymakers, and researchers.

Defining Conflict Prevention

This section of the handbook is devoted to developing a concept of conflict prevention that, while grounded in historical debates at the UN and AU, can be operationalized through concrete initiatives. This conceptual effort is based on three main premises. First, a coherent conceptual framework should lead to preventive responses that, rather than be implemented in a piecemeal manner, form part of a broader preventive approach. This requires linking the logic of prevention to the drivers of conflict across a broad time horizon—not just those limited to a specific country, but also those that cross its borders.

Second, recognizing that practice and research are linked, such a definition must be robust enough to help drive further research, including into areas that have not traditionally been considered as the “core” of conflict prevention and that either do or can serve as promising areas for innovation in prevention. This means that a definition of conflict prevention should not be so broad that it becomes all-encompassing, nor so narrow or rigid that it ends up reinforcing artificial distinctions and excluding innovative responses.

Third, a robust definition of conflict prevention must be grounded in (although not limited to) previous and ongoing debates, both in policy circles—including at the UN and the AU—and in the academic scholarship, even as it breaks the confines of those discussions by addressing local perspectives, demands, and concerns.

A necessary starting point for thinking about conflict prevention is a working definition of conflict itself. While several different definitions have been proposed in the past few decades, in this handbook we consider conflict to refer to: protracted disputes among social groups, whether inter- or intra-state, that threaten peace and security, hamper development, and negatively impact the well-being of a population. Typically, such friction emerges when the beliefs or actions of one or more members of the group are resisted, resented, or considered to be unacceptable to other group members, and it leads to outcomes that hamper the security and well-being of the society. Armed conflict is thus only the more extreme form of conflict, and can manifest itself in a variety of ways and among a broad set of actors.

Far from linear, conflict refers be a complex set of social interactions that are subject to escalation, eruption, transformation, and/or recurrence, and that therefore can also experience periods of “latency,” in which underlying antagonisms and other root causes temporarily become less salient but remain essentially unresolved. In such settings, it may take only a small trigger for long-held resentments to rise to the surface and escalate into broad violence.

Conflict, in other words, represents different forms and levels of risk and threatens a population’s security and well-being. This should be distinguished from disputes that have institutionalized resolution mechanisms, such as democratic and inclusive political processes. Although democratic societies are not exempt from violent conflict, research has shown that countries marked by strong records of respect for democracy and human rights have a far lower probability of experiencing civil war[i]. In the absence of such mechanisms, disputes are likelier to generate long-term resentment and adversarial behavior.

Therefore, in this handbook, we define conflict prevention as the combined set of tools, actions, and approaches designed to prevent the onset of armed conflict, and/or its recurrence by tackling both the root causes of conflict and its immediate triggers, both endemic and external to that setting. In this context, conflict prevention has three pillars: operational, structural, and transnational.

Key Policy Debates and Initiatives

There is growing interest on the part of multilateral organizations, donors, and other stakeholders in identifying innovations in conflict prevention—new approaches, practices, technologies, and mechanisms that render prevention more effective. One of the main challenges in doing so, however, has to do with the lack of conceptual clarity around conflict prevention. The idea has become excessively broad, making it difficult to translate it into concrete and coherent policies, recommendations, and approaches in the field. Conflict prevention has also become excessively abstract; although a multitude of preventive initiatives are already in place around the world, we know little about what works, when, and why. The relative lack of evidence-based research on conflict prevention helps fuel skepticism about the effectiveness of this approach.

The task of boosting conflict prevention in concrete, feasible ways also faces a number of political sensitivities, for instance concerns on the part of some UN and AU member states that stressing the concept could reinforce securitization at the expense of attention to, and resources for, core development and human rights work. Some member states have argued, more specifically, that this securitization trend threatens resources dedicated to development and human rights by channeling them towards the security pillar of the UN. Some stakeholders also believe that conflict prevention has been too narrowly associated with the concept of state fragility, and that, as a result, related efforts focus on low-income and conflict-affected states without paying due attention to the role that advanced economies often play in triggering or escalating armed conflict. In some cases, member states fear being stigmatized by conflict prevention, even when there is widespread acknowledgement among local stakeholders that more preventive action is needed.

The excessively narrow focus on fragile or “failed” states leads to distortions, in part because it fosters a highly selective view of conflict prevention and tends to overlook the role of transnational drivers, from nuclear proliferation and arms flows to geopolitical meddling and military interventionism. Signs of fragmentation and conflict in Europe, recurring tensions over nuclear programs, continuing arms races, and maritime disputes in the Pacific are all reminders that the idea of conflict prevention should not be constrained to low and middle-income countries. Every member state has a responsibility to promote prevention, whether by launching initiatives in its own territory, by refraining from triggering or exacerbating conflict elsewhere (for instance, in pursuit of geopolitical interests), or by contributing towards multilateral efforts at conflict prevention.

a. Conflict Prevention at the UN

The concept of conflict prevention became more visible in policy and academic debates during the 1990s, in the aftermath the Cold War and in the context of a sharp increase in the number of intra-state armed conflicts[x]. At the UN, the idea of conflict prevention had been not an afterthought, but in fact a central driver behind the creation of the organization. In October 24, 1945, when member states founded the new institution, their primary objective was to help ensure that the world would never again see the horrors of the World Wars and the Holocaust. This preoccupation echoed the concern with the maintenance of world peace that drove the creation of the League of Nations in January 1920, in the aftermath of the First World War. The idea of systemic prevention was, at the time, nothing short of revolutionary; while states had banded together in concerts in previous periods, those were more often belligerent alliances within volatile balance-of-power contexts rather than multilateral commitments towards stability. The failure to stop World War II was, correspondingly, viewed as a resounding failure of prevention by the collective security system.

During the founding of the UN, an added concern was thus superimposed on the desire to prevent the outbreak of another massive conflict: that of effectiveness. Given that the League had essentially failed in its primary goal of preventing large-scale war, how could the new organization incorporate more effective preventive mechanisms and approaches? How, and to what extent, could member states repeat the design and political mistakes embedded in the League of Nations? During the debates leading to the establishment of the UN, the comparison with its predecessor was a recurring theme and strongly (if implicitly) influenced the wording of the UN Charter. In these efforts, the single biggest shared concern revolved around the development of conflict resolution mechanisms that would help avoid another world war through a broader and more ambitious collective security system.

This concern with effective conflict prevention is therefore built into the first article in Chapter 1 of the UN Charter, which states that the maintenance of international peace and the adoption of collective preventive actions in order to achieve that peace are among the UN’s main purposes.[xi]

However, the centrality of this concept lost steam during the Cold War as much of the UN architecture, especially in peace and security issues, remained paralyzed by the East-West ideological divide, stymied by inter-state disputes, or instrumentalized by the superpowers. The UN Security Council, in particular, found itself by and large in a stalemate situation, even as important processes such as decolonization, the human rights agenda, and the creation of new platforms for the developing world advanced. This meant that, even as the UN accumulated some significant achievements in terms promoting people’s rights and well-being, its peace and security architecture remained ineffective in the prevention of conflict, especially open armed conflict. In those instances when the UN did become directly involved in open conflict, as in the case of Korea, the preventive dimension of its engagement was (and remains to this day) hotly disputed, with interpretations ranging from a police operation to a US-orchestrated and self-interested intervention. Even at the discursive level, the concept of conflict prevention lost steam amidst geopolitical wrangling in peace and security.

A related problem was the development of “silos” or excessively rigid separation between the peace and security, development, and human rights pillars, and even among divisions within each pillar. The organizational rigidity of this structure grew over time, hampering cross-cutting discussions and integrated approaches to deal with the drivers of conflict in different parts of the world.

Even though the UN was established as part of a broader network of multilateral organizations that also included the Bretton Woods institutions, it seldom collaborated directly with the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and other components of this loose system. Despite conflict prevention being at the core of all of these organizations, a division of labor developed that, with few exceptions, widened the gaps between the UN and other institutions. One of the biggest such lacuna was in conflict prevention; it for instance, it would take another seven decades before the UN and the World Bank began working more systematically on efforts to address the drivers of conflict.

It was only with the fall of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War that conflict prevention re-enter the UN agenda more forcefully, and almost strictly at the conceptual level. The 1990s provided a turning point for the idea of conflict prevention, as major UN failures in peace and security pushed member states and other stakeholders to demand that prevention of armed conflicts and humanitarian crises be pushed once again to the core of UN policy debates. In particular, the catastrophic failure of the UN in stopping the 1994 Rwanda genocide despite repeated warnings that a major humanitarian crisis was about to unfold, provoked renewed discussion of conflict prevention through multilateralism. New questions emerged about how the international community could become more proactive, rather than simply respond in limited fashion and far too late in major humanitarian catastrophes. It became clear that deep changes were needed, not just to the organizational structure of the UN, but in fact to its very culture. Implementing those changes, however, has turned out to be a decades-long struggle.

Partly due to the institutional inertia of such a large organization, which means that high-level leadership is needed to rally member states and the UN system itself for change, major policy debates on conflict prevention have been launched by the Secretaries-General. Boutros Boutros-Ghali (1992-1997) and Kofi Annan (1997-2007) both advocated for a greater focus on conflict prevention, albeit with somewhat different areas of focus. The most important document related to conflict prevention issued during Boutros-Ghali’s term was An Agenda for Peace (1992)[xii]. Not only did the Agenda underscore the importance of prevention, it also suggested a number of practical measures for boosting preventive measures, such as fact-finding missions and greater investment in economic development. Boutros-Ghali focused on the idea of preventive diplomacy, defined within the UN as “diplomatic action taken to prevent disputes from escalating into conflicts and to limit the spread of conflicts when they occur.” The concept also includes, more specifically, the use of envoys dispatched to crisis areas to promote dialogue, although preventive diplomacy may also involve actions by the UN Security Council, the Secretary-General, and other high-level officials during critical moments[xiii]. The concept, however, in general addresses imminent crises and conflict outbreaks, rather than their underlying drivers.

In the 1990s, Annan also urged the organization not only to incorporate conflict prevention at the top of its agenda but also to mainstream it throughout the UN pillars. During Annan’s mandate, the most significant documents related to conflict prevention included We the Peoples – The Role of the United Nations in the 21st Century (2000)[xiv], Report of the Panel on United Nations Peace Operations (2000) [xv], and the Report of the Secretary-General on Prevention of Armed Conflict (2001).[xvi] Broadly put, these reports stressed the need for a culture of prevention—a set of institutional norms and practices that prioritize and mainstream prevention rather than reaction—throughout the UN system. The idea of a culture of prevention suggests that a precautionary approach is internalized by actors operating at different levels within the architecture, rather than pigeonholed as a separate theme. However, a cultural shift does not take place spontaneously, without being grounded in specific and strategic reforms to the organization and prioritization of the concept in its official discourse. Without sufficient concrete steps, this call for cultural change results only in discursive shifts without corresponding action.

Ban Ki-moon (2007-2017)’s main contribution to the debates on conflict prevention was the series of reviews of UN’s peace and security architecture[xvii]—on UN peace operations, peacebuilding architecture, and global study on Women, Peace and Security. Rather than simply underscoring the importance of a preventive approach, these reviews offered specific recommendations to different parts of the UN system, as well as to the Secretariat. For instance, one of the resulting reports, the Report of the High-Level Panel on United Nations Peace Operations, also known as the HIPPO report(2015), recommended that the UN strengthen its capacity in conflict prevention and mediation in peace operations settings. The report included targeted suggestions for how responses may be better designed, coordinated, and implemented, besides addressing the need for better coordination for prevention. For instance, the report calls for increased collaboration between different parts of the UN system, as well as between the UN and its regional partners, as ways to provide more effective and holistic responses to conflicts.

The review on the Women, Peace and Security Agenda, initially launched at the UN through UNSC Resolution 1325, also proposed new ways to make the organization’s approach to conflict more preventive and effective. The review, which included an independent Global Study titled “Preventing Conflict, Transforming Justice, Securing the Peace” recommended more efforts to increase women’s meaningful participation in conflict prevention and peacebuilding, as well as ensure the protection of women’s human rights. The review and the study offered concrete, evidence-based links between women’s participation in efforts such as peace processes and increased probability of positive outcomes, such as the implementation of agreements and the prevention of conflict relapse. In addition to assessing the implementation of National Action Plans (NAPs), the review offered suggestions on how mainstreaming women’s participation can strengthen sustainable peace. The review thus represented a key landmark in the effort to stress the need for more inclusive conflict prevention and resolution—a debate that has now broadened to include more consideration of other groups, as per the emerging UN agenda on Youth, Peace and Security resulting from UNSC Resolution 2250 (2015).

Another report coming from the reviews was developed by the Advisory Group of Experts (AGE) as part of the review of the UN peacebuilding architecture. The AGE report introduced the idea of Sustaining Peace and resulted in both the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) and the General Assembly (UNGA) adopting identical resolutions on the matter in April 2016. Sustaining Peace, in this context, is presented as a vision that provides a new rationale and renewed momentum for responding to conflicts. The vision seeks to move the UN and its partner organizations away from linear responses to conflicts, bringing conflict prevention and peacebuilding together as complementary processes in the quest by the international community to prevent conflicts and sustain peace[xviii]. These ideas emerging out of the three reviews faced three key challenges: gathering support among member states, drawing interest and commitment from across the UN system, and securing high-level leadership, especially given that Ban’s mandate was coming to an end. Without these three elements, the reviews ran the risk of losing steam and being effectively shelved as UN leadership changed.

Rather than abandon the efforts and reformative spirit of the three reviews, Ban’s successor, António Guterres (2017-present), chose to provide further momentum to this emerging process. He used the initial months of his mandate, when SGs typically have high political capital, to raise the banner of conflict prevention and launch with new impetus discussions of the UN’s effectiveness. Guterres has built on the recommendations and resolutions resulting from the three review processes launched by his predecessor. He has highlighted conflict prevention as the top priority for the UN and has spoken of the need for a “whole new approach” in his speeches—signaling that, rather than doing more of the same as in the past, the UN should become more open to (and indeed, foment) change and policy innovation in its vision of Sustaining Peace.[xix]

With respect to the historical problem of the “silos” and the challenges they pose to addressing the drivers of conflict, Guterres has called for the development of “a comprehensive, modern, and effective operational peace architecture, encompassing prevention, conflict resolution, peacekeeping, peacebuilding and long-term development—the ‘peace continuum’”. He has stressed that prevention—far from being the sole domain of peace and security—must be integrated into the three pillars of the UN’s work[xx]. In strengthening the interlinkages between peace and security, development, and human rights, this point contributes towards breaking down the excessive separations that can result in an uncoordinated approach by components of the UN system, even when they are operating in the same context.

This discursive shift—not only highlighting conflict prevention, but making it more multi-dimensional—has been accompanied by recommendations for organizational changes. During the first year of Guterres’ mandate, a joint effort by the UN and the World Bank resulted in a report titled Pathways for Peace: Inclusive Approaches to Preventing Violent Conflict. The report, launched in September 2017, marks the first substantial partnership between these two institutions—both originally created with the express mandate of preventing conflict—on promoting concrete ways of avoiding the outbreak or recurrence of armed conflict[xxi]. Pathways for Peace argues that development processes must be better articulated with diplomacy and mediation, security, and other tools designed to prevent conflict from becoming violent. It includes case studies of several countries and institutions as part of a drive to identify promising initiatives and to build the case that more effort is needed to “address grievances around exclusion from access to power, opportunity and security.” Pathways to Peace represents an important landmark in the relationship between the UN and the World Bank, in that—after seventy years of mostly parallel work—their prevention debates and initiatives finally begin to dovetail. However, the report focuses heavily on state fragility and cases drawn from the developing world, granting less attention to transnational factors and the roles played by advanced economies.

Besides these efforts led by the UN Secretaries-General, there have also been a number of preventive initiatives by the UNSC, especially in terms of immediate and reactive actions. While most UNSC resolutions focus on managing incipient and ongoing armed conflicts by deploying peacekeeping operations,[xxii] the UNSC has also issued resolutions on preventing armed conflict. For instance, UNSC resolution 1366 (2001) stresses the body’s role in preventive actions, recognizing the linkage between conflict prevention and development, the importance of the Secretary-General in this area, and the need for a conflict prevention strategy.[xiii] In recent years, some innovations and new working methods have been introduced, such as Horizon Scanning Briefings, but mostly on an ad hoc basis. Broadly put, UNSC-led efforts in conflict prevention have been piecemeal, and the geopolitical interests shaping the Council, especially those revolving around the P-5 (the five permanent members with veto power), mean that it is often unable (or unwilling) to prevent conflicts, as in the case of Syria[xxiv]. This geopolitical dimension of the UNSC also means that the role of P-5 states in contributing towards armed conflict (especially through initiatives outside the scope of the UN) receives little attention in UNSC debates—and, more broadly, within the UN peace and security architecture). In turn, this selectivity has strengthened the narrow association between conflict prevention and the “failed state” narrative.

Major normative shifts on intervention have also been relevant to debates about conflict prevention. In 2005, member states endorsed the principle of the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) for humanitarian interventions as a way to prevent genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing, and crimes against humanity.[xxv] The International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty (CISS), an ad hoc group of General Assembly members convened by the Canadian government, stressed that R2P has three main responsibilities regarding armed conflict: to prevent, to react, and to rebuild. The concept has been influential in that it demands stronger action from UN member states in preventing large-scale human rights abuses and crimes against humanity, and that it provides a broadened gamut of justifications for intervention. However, academic and policy discussions around R2P have often focused on reaction and rebuilding, paying relatively little attention to the principle’s potential for preventing conflict. Bellamy (2008) has argued that this omission is in part a result of disagreements over the breadth of the idea of prevention, as well as political sensitivities over associating prevention with combating terrorism[xvi].

In addition, consensus around R2P has weakened since the early 2010s as backlash emerged to the intervention in Libya. Many UN member states, including Brazil, India, Russia, China and South Africa (all members of the BRICS coalition), have at times expressed misgivings about R2P, arguing that the principle can be invoked selectively to advance the geopolitical interests of P-5 states. These countries have also noted that the implementation of R2P can produce uncertain and undesirable results, especially when regime change is involved, as in the case of the intervention in Libya. Proposals by some of these countries to temper the principle of R2P have included the idea (put forth by Brazilian diplomats) of the Responsibility while Protecting (RwP), which attempts to curb the interventionist momentum of R2P. In June 2012, researchers from Chinese think tanks, some of them linked to the government, put forth a semi-official proposal for the concept of “Responsible Protection,” which stresses the primacy of the first two pillars. However, the implications of these normative proposals—beyond casting doubt on the application of R2P and, more broadly, on the motivations behind humanitarian intervention—remain hazy.

Another relevant debate concerns the role that peace operations play in conflict prevention. Regarding peacekeeping, there have been calls for UN peace operations to assume more preventive approaches rather than focus narrowly (as they often have) on conflict management—a set of practices and responses meant to prevent escalation and spillover but not necessarily geared towards (of capable of) resolving the conflict. Although conflict prevention is an overarching goal of UN peace operations, peacekeeping is often designed as a means to manage conflicts, de-escalating tensions and preventing spillover into neighboring countries. Within the context of specific missions, the effective protection of civilians and other efforts meant to stop escalation and recurrence of armed conflict also require creating the conditions necessary for political solutions to move forward. Guterres has noted at the UNSC that peacekeeping is “a tool to create the space for a nationally-owned political solution,” and that unrealistic demands on UN peacekeeping costs both lives and credibility. The links between conflict management via peacekeeping and conflict resolution, especially via peace processes, remain highly variable and under-studied.

Debates have also intensified over the effectiveness of peacekeeping, spurred in part by new budgetary pressures that have led to the termination of some missions and cuts in others. While some observers argue that these cuts will adversely affect peace operations, others defend that cost-cutting may in fact spur more efficiency and innovation, such as through enhanced partnerships with regional organizations like the AU, or in harmonizing efforts with ad hoc security initiatives such as the G-5 Sahel group (created by Mauritania, Mali, Niger, Chad and Burkina Faso and supported by France). The call to promote innovation in aspects such as regional partnerships, mandate design and peacekeeping training often walks a tenuous line between pushing for more preventive capacity and, on the other hand, acknowledging that not all mechanisms within the UN peace and security architecture should be tasked with a primary preventive responsibility.

Debates around the preventative role are even more relevant to the UN’s special political missions, especially through the organization’s efforts to support political processes and mediation. While these missions vary widely in their roles, scope, and characteristics, they are a key platform for preventive diplomacy and other activities meant to help prevent and resolve conflicts and support complex political transitions, in coordination with national actors and UN development and humanitarian entities on the ground. Mediation efforts include advisory financial and logistical support to peace processes; working to strengthen the mediation capacity of regional and sub-regional organizations; and serving as a repository of knowledge, policy and guidance, lessons learned and best practices. The Department of Political Affairs, for instance, manages the UN Standby Team of Mediation Experts, an on-call group established in 2008 that can be quickly deployed to assist mediators and help de-escalate tensions. Political missions are also important in articulating with special envoys and advisers of the Secretary-General that work to bring his “good offices” for the prevention of escalation, the resolution of conflicts, or the implementation of other UN mandates, as well as fact-finding missions and investigative initiatives. As of 2017, the UN counted ten field-based missions; three field-based missions serving multiple countries; ten special envoys, advisers and representatives; and twelve sanctions panels and monitoring groups[xxvii].

In some missions, especially that in Colombia, the UN (both the mission and the UN funds, programmes, specialized agencies already established in the country) have played a vital but non-protagonist role in boosting institutional capacity for conflict prevention and resolution. The implementation of the peace agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC has been nationally-led, offering an innovative model for the UN to promote preventive capacity in middle-income countries (MICs). However, this approach may not be suitable to engage in conflict prevention in states with greater state fragility, as is the case of Guinea-Bissau, where the UN mission (UNIOGBIS) has worked to support not only national-level processes but also local mediation and peacebuilding mechanisms.

The excessive distance between the UN’s political functions and its peacekeeping mechanisms—each of which has been managed by a different division of the UN—has sometimes undermined the organization’s preventive capacity. This point has been acknowledged within the scope of the organizational reforms announced by Guterres in 2017. Although precise changes are still being debated at the time of this writing, proposed changes include closer structural linkages between the Department of Peacekeeping Affairs (DPKO) and the Department of Political Affairs (DPA). Creating such bridges may be an opportunity to better streamline practices that are currently fragmented across different organizational divisions, and which possibly undermine conflict prevention initiatives in the field. Fostering cross-pollination between these and other divisions involved in conflict prevention may also allow for more productive discussions of lessons learned and innovative solutions.

More broadly, a more coordinated and comprehensive approach may help the UN to devise more effective preventive strategies by identifying and meeting demands more effectively, and by avoiding duplication of efforts. So may special measures targeting specific problem areas, such as those proposed to improve the UN’s approach to preventing and responding to sexual exploitation and abuse; to boost the UN’s capacity to assist member states in implementing the UN Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy; and repositioning the UN development system to deliver on the 2030 Agenda[xviii].

The idea of making the UN approach more coherent and effective also applies to the Peacebuilding Architecture. Since the mid-2000s, major discursive shifts and some organizational innovations around the idea of promoting peace have taken place at the UN, with important consequences for its approach to conflict prevention—not only its capacities but also its limitations. At the 2005 World Summit, held in September at UN New York headquarters, more than 170 member states agreed upon the creation of the UN Peacebuilding Commission (PBC). The PBC was formed as an intergovernmental advisory board and as a subsidiary organ of both the UNSC and the UNGA to support peace efforts in conflict-affected countries. The move reflected the realization that the structure of the UN, and especially the divide between its security and development pillars, tended to stymie innovative thinking around the nexus between these two fields, including as it relates to conflict prevention.

Although the creation of the PBC can be viewed as an important step in the incremental reform of the UN architecture and its preventive capacity, it has largely focused on proposing actions in specific countries emerging from conflicts. The recommendations issued in 2016 by the AGE report underscored the need to address the “root causes of conflict” through long-term commitment and reliable funding[i]. However, the PBC’s open-ended funding, its position as subordinate to and limited interaction with the UNSC, and its lack of a mandate for effective actions all pose significant challenges towards boosting the peacebuilding architecture’s capacity to promote conflict prevention more broadly. Due to these limitations, at the UN the term peacebuilding has become associated with a rather narrow range of activities conducted by this architecture, although the portfolio of initiatives undertaken through the Country-Specific Configurations offers a wealth of innovative solutions, not only at the national level but also at more local ones. Likewise, the Peacebuilding Fund, designed to deliver fast, flexible and relevant funding, offers lessons on how to make resources available under fast-changing circumstances so as to decrease the probability of imminent crises and conflict relapses. In conjunction with the Peacebuilding Support Office (PBSO), these elements of this architecture represent one of the key platforms in the promotion of the Sustaining Peace vision[ii].

The UN development system and humanitarian agencies also carry out a broad gamut of activities related to conflict prevention, although they are not always labeled as such. On the humanitarian front, there are ongoing debates about the extent to which the humanitarian parts of this system should engage with long-term prevention (including via development efforts) rather than focus more narrowly on emergency assistance to populations affected by war and conflict. Proponents of linking these spheres argue that there is a need to bridge and create greater synergies between short-term measures and longer-term development initiatives. Critics, however, defend that these two spheres are premised on somewhat different mandates and principles, and that linking them may imperil the success of both, including with respect to the UN and partner organizations’ capacity to prevent conflict.

The preventive engagement and capacity of the UN development system vary widely across its forty-plus programs, agencies and funds within the system. It may be that many activities long carried out by these components of the system are only now being reframed as conflict prevention due to the increased salience of related debates within the UN, especially given the breadth of the term as it has been used in UN discussions. In other instances, as the case of the UN Office for South-South cooperation, there is an incipient but growing effort to rethink the office’s activities in light of preventive capacity, including by engaging in areas in which the UN has not traditionally promoted South-South cooperation (SSC), such as mediation.

The launch of the Agenda 2030 has prompted more discussion about how to carry out conflict prevention and relate it to human rights as well as development activities. Whereas the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) left out issues of violence, conflict and fragility altogether, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) address these issues both directly (through SDG 16) and more indirectly by stressing the preventive potential of the other goals, from boosting education to supporting greater gender equality and empowering women and girls. SDG 16—focused on achieving peaceful, just, and inclusive societies—promotes the rule of law and access to justice, as well as citizen security and human rights, while also serving as an enabler for the other goals.

The agenda seems to have energized parts of the UN development system in a more preventive direction. The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), for instance, has worked to better align its initiatives with conflict prevention, especially in terms of addressing the root causes of conflict by tackling challenges such as state weakness, unemployment, and inequality[xxvi]. At the UNDP and elsewhere in the system, the SDGs have also promoted new discussions about conflict prevention and its ties to topics that did not always feature prominently in the UN development agenda, such as climate change, migration and refuge, and youth.

Despite these promising changes, there is no consensus yet regarding the links between the Agenda 2030 and conflict prevention more broadly (or, for that matter, the concept of Sustaining Peace). Some member states have pushed for a narrower definition of Sustaining Peace that practically makes it coterminous with the SDGs, while others have lobbied for a much broader concept that pushes the UN’s preventive capacity well beyond the scope of the goals and associated targets of Agenda 2030.

One area that is frequently overlooked in debates about conflict prevention but that has gained increasing attention, both within the UN and outside of it, is South-South cooperation (SSC) and triangular cooperation (TC), which refers broadly to cooperation efforts among states or other actors from the Global South, and which are implemented according to somewhat different principles than “traditional” aid. These principles include horizontality, solidarity, and non-conditionality. South-South cooperation encompasses a broad range of initiatives, such as social policy efforts in education, health, and agriculture; trade and investment, including in infrastructure; and science and technology. In some areas, SSC partners work to catalyze sectoral change by investing strategically in institutional capacity-building and networks. Triangle cooperation entails a trilateral arrangement between two developing countries and a third party, which may be a donor country, an international organization, or a third developing country. In areas where protagonism by donor states or international organizations (including the UN) may be viewed as interference by external actors, triangular cooperation (and, more broadly, SSC) may offer a way to make conflict prevention more politically acceptable to local and national actors.

At the UN, especially due to efforts launched in 2017 by the UN Office of South-South Cooperation (UNOSSC) and the DPA, the relevance of SSC to peacebuilding and, more broadly to conflict prevention, is becoming more visible at the UN. However, debates about the potential contribution of SSC to conflict prevention at the UN are still incipient. Discussions of the potentials and pitfalls of different modalities like economic, technical, educational and scientific cooperation are deepening primarily in non-UN platforms such as the BRICS, the China-led Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), sometimes referred to as the New Silk Road, and the Fragile-to Fragile cooperation promoted by the G7+.

In order to strengthen the UN’s preventive capacity, Guterres has also worked to build on the efforts of Ban Ki-moon to boost the Human Rights up Front (HRuF) initiative. HRuF initially emerged out of the recognition that the UN—both the Secretariat and the country team—failed in the last phase of the Sri Lankan civil war, in part due to the fragmented efforts of different agencies in addressing the conflict. This instance of systemic failure led to efforts to create a broad solution that would enable the mainstreaming of human rights into the work of all UN staff and improve early warning and coordination mechanisms. By cutting across the three UN pillars, HRuF is intended to trigger a cultural change within the UN system in the direction of greater awareness and courage in preventing serious and large-scale human rights violations. In addition to this effort to engage more consistently with conflict prevention in the sense of preventing genocides and other mass atrocities, the human rights pillar of the UN can be said to contribute to the organization’s capacity by promoting more inclusive political processes as well as respect for rights and the rule of law. By breaking cycles of abuse, impunity, and resentment, protection of human rights supports conflict prevention at multiple levels. However, as UN officials have acknowledged, there is still much work to be done in boosting the preventive dimension of measures such as institutional reforms to strengthen judicial independence, establishing civilian oversight over security forces, or supporting changes in policing strategies[xxvii].

Certain topics that cut across all three pillars of the UN have gained visibility at the UN and partner organizations but also been the subject of heated debates regarding their role in conflict prevention, such as violent extremism. In addition, although many peacekeeping missions are affected by violent extremism, as in the case of Somalia (AMISOM) and Mali (MINUSMA), there are serious questions regarding UN peacekeeping capacity to deal directly with this type of threat[xxviii]. Therefore, the links between combating violent extremism and conflict prevention within the scope of the organization remain unclear at the conceptual and operational levels.

Conflict Prevention at the AU and the Regional Economic Communities (RECs)

Since its launch on May 26, 2001, the AU has worked to develop more effective African responses to conflicts. The 1990s crises in Rwanda and Somalia in particular, brought the realization that—since the broader international community, including the UN—often proved unable or unwilling to respond to emerging conflicts, Africa had to become better equipped to respond to its own crises. As a result, the AU emerged out of the older Organisation for African Unity (OAU), moving away from the traditional pillar of non-interference, towards the idea of non-indifference, whereby the AU is allowed to intervene in member countries to stop grave atrocities like war crimes and genocides. Therefore, much as in the case of the UN, the AU also had conflict prevention as a key objective from the very start, but with a strong emphasis on African ownership of solutions, as reflected in the oft-repeated phrase “African solutions for African problems.”

The AU’s Constitutive Act provides a solid normative framework for pursuing an effective peace and security agenda, but concrete mechanisms must be developed to ensure that its ideals are met. Toward this end, the AU has developed a series of mechanisms meant to allow the organization to better respond to conflicts. In particular, the creation of the AU Peace and Security Council (PSC),one of the components of the African Peace and Security Architecture (APSA), has received increasing attention as a way to provide effective and timely responses to emerging crises. The PSC has, among its foundational protocol, the task of anticipating and preventing disputes and conflicts, as well as policies that may lead to genocide and crimes against humanity. Its core functions include early warning and preventive diplomacy, facilitation of peace-making, peace-support operations and, in some instances, recommending intervention in member states so as to promote peace, security, and stability. Finally, the PSC supports peacebuilding and post-conflict reconstruction, as well as humanitarian action and disaster management.

Conflict prevention at the AU has both operational components, meant to address imminent or escalating conflict, and structural components, designed to tackle deeper causes of conflict. Operational conflict prevention at the AU entails actions that are normally taken during the escalation phase of a given conflict, when proximate, dynamic factors come into play.[xxix] Mechanisms include the Continental Early Warning System (CEWS), which is one of the five pillars of the APSA and tasked with data collection and analysis, as well as related collaboration with the UN system and other international partners so as to provide inputs to the PSC on potential conflicts and threats of peace and security and to recommend the best course of action. Other elements include mediation and the role of the Panel of the Wise (PoW), a five-person panel of “highly respected African personalities from various segments of society who have made outstanding contributions to the cause of peace, security, and development on the continent” and who are tasked with supporting the PSC and the AU Commission, especially in conflict prevention.

In 2014, the AU structural prevention framework was approved. Structural prevention in this context is designed to reduce the likelihood of conflict and violence through efforts to strengthen the resilience of African societies and provide access to political, economic, social and cultural opportunities.[xxx] A May 2015 AU communiqué underscored that good governance through the strengthening of democratic culture and institutions, respect for human rights, upholding the rule of law, and socio-economic development are needed to prevent conflicts and foster peace and stability in Africa. It also stressed the need for a “comprehensive and holistic approach” to conflict prevention that includes building strong, responsive and accountable state institutions at national and local levels that deliver key services, and for ensuring inclusive political processes and economic empowerment, rule of law and public security.

While both approaches to conflict prevention—operational and structural—have gained prominence at the AU political levels, there are still considerable challenges in ensuring their effective implementation and to attain the goal of ensuring that “all guns are silenced” by 2020. First, there are disputes around where are the leading points around conflict prevention efforts, including mediation. For instance, two divisions within the AU peace and security department—namely the Crisis Management and Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Development (CMPRD) and the Conflict Prevention and Early Warning (CPEW) —often are seen as key entry points for conflict prevention initiatives, including mediation, peacebuilding, and political accompaniment to countries. In addition, the linkages between the AU Department of Peace and Security and Department of Political Affairs are still incipient. Yet another overarching issue is the AU’s continued reliance on donor countries for funding, which subjects the organization to budget cuts and may make it more vulnerable to those states’ political agendas. These gaps mean that recurring problems such as contested government transitions continue to trigger recurring conflict in many parts of the continent.

In a bid to improve, the AU has also worked to build closer ties to the Regional Economic Communities (RECs), which include eight subregional bodies, considered to be the “building blocks” for AU integration. Normative and operational approaches to conflict prevention developed at the AU also depend on harmonization with these entities in order to reach the continent’s different subregions. The RECs not only play a vital role in several transformative programs for Africa, such as as the 2001 New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NEPAD) and the First Ten-Year Implementation Plan, adopted in 2015, but also have important role in the continent’s peace and security agenda. Because the RECs work with governments, civil society and the AU Commission in implementing broad frameworks such as Agenda 2063, a strategic framework that seeks to accelerate the implementation of continental initiatives for growth and sustainable development in Africa over a 50-year period. they are essential in achieving conflict prevention objectives. However, the capacity and scope of the RECs vary widely, and some have been heavily shaped by subregional geopolitical forces that sometimes detract from their preventive capacity.

In 2011, the AU developed the African Governance Architecture (AGA), which acknowledges the role of governance in enhancing conflict prevention efforts. While most in Addis Ababa Headquarters acknowledge the complementarity between AGA—which brings together AU organs and Regional Economic Communities (RECs) working on democratic governance and human rights —and APSA, there is still little interaction between the two architectures in implementing conflict prevention.

The AU Commission has also developed processes designed to enhance its conflict prevention capacity and complementarity. If effectively implemented, the interdepartmental working groups on Post-Conflict Reconstruction and Development (PCRD) and on structural prevention can create new opportunities for the AUC to further enhance collaboration. Finally, new opportunities for conflict prevention may emerge through continued discussions between the AU and REC/RMs on the implementation of APSA goals, including through its linkages to African Agenda 2063.

A Typology of Conflict Prevention Approaches

Beyond the Structural/Operational Dichotomy

Many existing typologies of conflict prevention[xxxi] differentiate between immediate causes of conflict and deeper, structural drivers. While separating these two categories of drivers may seem artificial—in practice, many responses may address immediate and structural causes of conflict simultaneously—these ideal types provide a basic organizing logic for thinking about (and designing) responses that address key factors. The AU’s division between operational and structural prevention reflects this logic. While it is widely acknowledged that these are not hard categories—in other words, many drivers (and therefore, solutions) straddle the divide—our conceptual approach seeks to distinguish between underlying or root causes of conflict, and the more immediate disputes and escalation dynamics that can erupt in armed violence.

The dichotomous approach of immediate/structural prevention has been influenced by the heavy focus on the idea of the fragile state—or, in its more extreme version, that of the failed state. While the idea of state fragility is deeply institutionalized within the World Bank and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), it has also been influential in UN and AU debates about conflict prevention. The OECD, for instance, has been publishing a report on Fragile States every year since the inaugural issue came out in 2005; the report is designed to “monitor aid to a list of countries that are considered most fragile.” In 2015, this approach underwent a shift in that the organization proposed an understanding of fragility that goes beyond fragile and conflict-affected states, as reflected in the “States of Fragility Report.” However, these two institutions mostly rely on the concept of fragility to come up with lists, rankings, and other hard categories used to define the level (and, to some extent, the type) of aid—especially development assistance—that is made available to individual states.

Although the concept of state fragility has also been influential at the UN and AU, the SDGs have created new pressures to think about the drivers of fragility—including conflict—beyond these categories. More specifically, SDG 16 aims to reduce violence of all forms in all countries, rather than simply those labeled as fragile. This idea not only widens the understanding of what causes fragility, but also broadens expectations about how states—and, more generally, the international community—should tackle these issues, including conflict.

The focus, however, has remained on individual member states as the main level of analysis—and therefore, of policy response. Areas such as political, economic, socio-cultural, and institutional conflict drivers are analyzed, and responses are designed for each of these areas, or (less commonly) in a more integrated approach that attempts to tackle several drivers at once, as in the case of inclusive growth strategies.

As a result, close attention has been paid to factors that are either endogenous to a country or that manifest themselves primarily within that territorial space. Yet most conflict today, including those in Africa, entail different and intertwined layers of drivers, from the local to the subnational to the national and the regional, as well as transnational factors. The latter includes not only organized crime in all its varieties (traffic of drugs, people, and arms), terrorism, and associated activities such as corruption and money laundering. These are linked in complex and often mutually reinforcing ways, and they both take advantage of institutional weaknesses caused by conflict, and contribute to those phenomena. In addition, geopolitical meddling—whether by other regional actors or by global powers—can have a deep and lasting destabilizing effect on countries, contributing towards the spread of conflict.

In addition to making conflict prevention more effective, taking into account these transnational drivers of conflict has political significance: doing so opens up new space for making the conflict prevention agenda truly universal, rather than narrowly associated with conflict-affected low-income states. This universality is very much in line with the spirit of Sustaining Peace and the call on all actors, including member states and regional organizations, to take on responsibility in the prevention of conflict.

A typology of conflict prevention should thus capture not only the operational/structural dichotomy but in fact include a third dimension that acknowledges broader, transnational dynamics—including geopolitical disputes—as drivers of conflict. In the typology below, we refer to this third column as Transnational Prevention in order to acknowledge not only the role that such phenomena play in creating and exacerbating conflict, but also the key role that subregional, regional and global initiatives play (or should play) in conflict prevention, whether through ad hoc initiatives, ongoing efforts, or normative efforts meant to curb the emergence or recurrence of conflict.

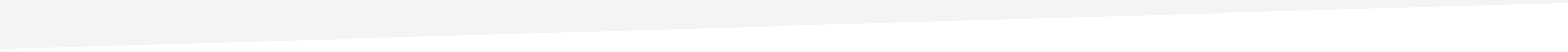

Table 1. A Typology of Conflict Prevention

All three types of conflict prevention proposed in this typology—operational, structural and transnational—require collaboration between a wide variety of stakeholders, but the third, in particular, demands coherent and sustained responses through transnational arrangements. All of the actions included in this column require international cooperation between states, civil society, and private sector entities. Ideally, they are coordinated with national and subnational-level responses, especially as those relate to structural prevention.

There are also elements of conflict prevention that cut across all categories, namely human rights and inclusiveness. In the next section, we hone in on one aspect of inclusiveness that has demonstrably enhanced all three categories of conflict prevention (immediate, structural and transnational): mainstreaming gender in conflict prevention.

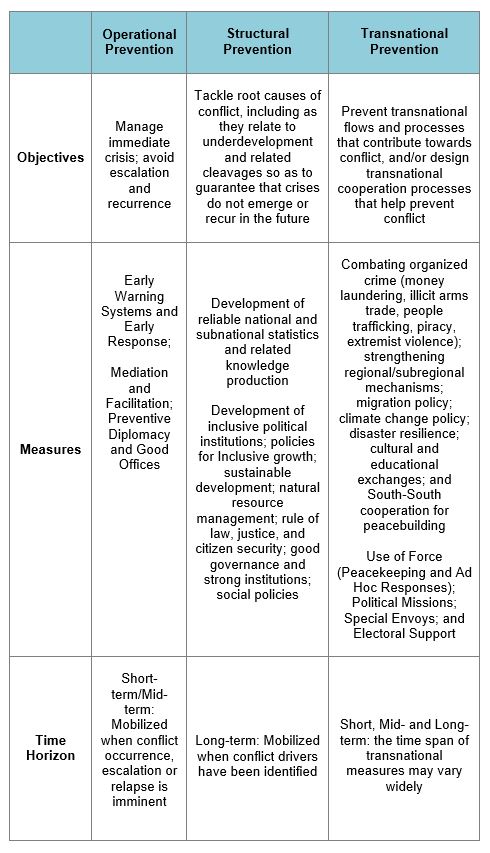

In the Conflict Prevention Database built by Instituto Igarapé as part of the ICP initiative, the typology yielded the following categories and subcategories[i].

[i] These categories will expand as more projects enter the database.

Table 2. ICP Conflict Prevention Database Project Categories

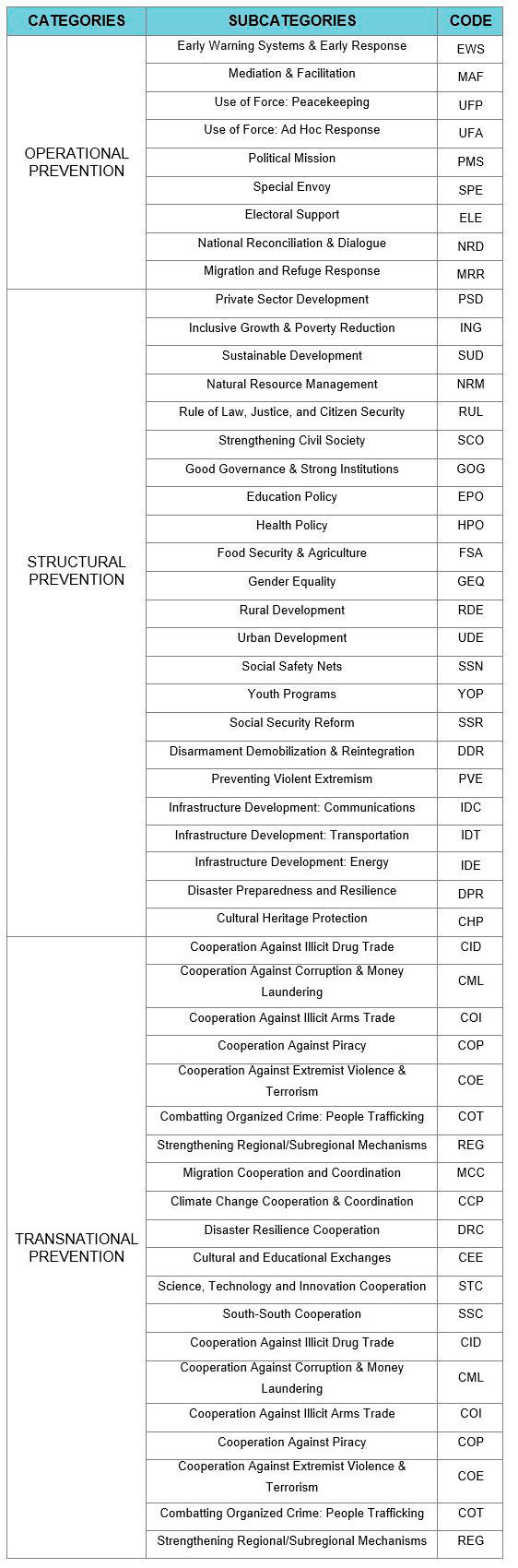

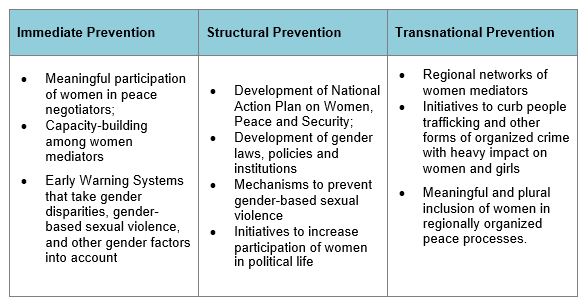

Mainstreaming Gender in Conflict Prevention

The typology of conflict prevention proposed here mainstreams gender rather than treat it as a niche topic, although gender-specific responses can also be included under the rubric “social policies” as part of structural prevention. The idea is that all responses—whether they fall under operational, structural or transnational prevention or straddle categories—both entail the meaningful inclusion of women and adopt a gender lens.

The recent scholarly literature on gender and security recognizes that women and, more broadly, gender play key roles in conflict, as well as conflict prevention and resolution. As a key determinant of individual and group identities alongside ethnicity, class, age, race and religion, gender deeply shapes the experiences of people in conflict-affected settings. In the case of women and girls, while they have traditionally been portrayed as victims of war and do tend to suffer disproportionately from certain types of violence, displacement, and dispossession, adopting a gender lens entails also acknowledging that women take on a wide gamut of roles, from combatants to mediators, peacekeepers and peacebuilders.

In addition to the social justice dimension, there are pragmatic reasons for promoting the meaningful participation of women and addressing gender issues in conflict prevention. A variety of recent studies indicate that standard peace-making methods, including Tract I peace negotiations, prove ineffective when women are left out or included only in a token manner. In one salient statistic, almost half of peace agreements signed in the 1990s failed within five years, with recidivism for civil war being particularly high. The inclusion of women (and women-centered civil society organizations) in such processes has been shown to reduce conflict and advance stability. According to one study, inclusion of women and civil society in a peace process renders the final agreement 64% less likely to fail; yet another study found that such agreements are 35% more likely to last at least fifteen years than those that failed to include women. Despite this proven impact, the participation of women in peace negotiation and other aspects of mediation and facilitation, to name only one type of response included in the conflict prevention typology presented here, remains minimal.

The importance of integrating women in conflict and peace initiatives has become more widely acknowledged at a global level, especially after the Fourth World Conference on Women, held in Beijing in 1995, and since Resolution 1325 (2000) of the UN Security Council called for increased access of women to conflict prevention and resolution. Resolution 1325 stated that gender-sensitive initiatives should involve women in all phases and mechanisms of peace agreements, and to ensure that the human rights of women and girls are respected. The ongoing development of National Action Plans (NAPs), including in many post-conflict or conflict-affected settings, can be understood as part of this effort to address the needs, demands, and roles of women in conflict-affected settings. Likewise, the AU (and consequently, the RECs) has adopted a number of initiatives on women, peace and security geared at enhancing the participation of women in conflict prevention and ensuring their inclusion in post-conflict institutions and processes. Ironically, even those institutions have been slow to incorporate women within their mediator ranks and other peacebuilding roles.

Gender mainstreaming is needed not only in operational prevention, but also in structural and transnational prevention. Without the inclusion of women and the incorporation of a gender lens in the design of social policies, in inclusive growth and in sustainable development, the gender gaps are likely to rebound even in armed conflict contexts where a peace agreement has been signed. Likewise, transnational prevention requires transnational and regional institutions to take gender seriously in order to develop and promote inclusiveness norms that help to sustain peace across borders.

In the context of this Handbook, gender mainstreaming in conflict prevention refers to the adoption of cross-cutting gender lens in the design, implementation, and monitoring and evaluation of conflict prevention responses, so as to address gender imbalances and incorporate an understanding of how gender affects conflict dynamics and vice-versa. Gender, in other words, is taken into account in all of the categories appearing in the Typology above, as well as in the ensuing case studies and analyses emerging out of this initiative.

We understand gender mainstreaming to be an essential component in the broader process of making conflict prevention more inclusive, which also entails incorporating the views, experiences, demands and concerns of other groups, such as youth, the elderly, and racial, ethnic and religious minorities.

Table 3. Examples of Gender-Sensitive Conflict Prevention Measures

Moving Forward

This handbook is intended to move the discussion of conflict prevention in a more concrete and innovative direction by offering conceptual tools, especially the typology covering immediate, structural, and transnational responses. The typology forms the basis for the ICP Conflict Prevention Database which, coupled with the text-based outputs from the project, aims to help policymakers, practitioners, researchers, and other stakeholders map, analyze, and draw inspiration from specific examples of conflict prevention efforts in parts of the African continent.

The exercise offers the following take-away points:

- Although the international community has focused heavily on the immediate side of conflict prevention, using tools such as mediation and good offices to prevent the imminent breakout or intensification of conflict, more attention is needed to structural prevention, with a longer-term view and corresponding policy approaches.

- Despite the heavy focus on individual states, conflict prevention requires greater attention to transnational factors, whether at the regional or global level. From arms flows to migratory fluxes and geopolitical meddling, transnational factors demand far more innovative international cooperation on conflict prevention.

- Given the evidence on how inclusive processes contribute towards positive peace, all types of conflict prevention responses – primarily whether immediate, structural or transnational – should incorporate the perspective, and attend to the needs, of population groups that are particularly vulnerable in conflict-affected contexts, including women, children, the elderly, and ethnic or religious minorities.

- Although global and regional epistemic communities have emerged around specific categories of conflict prevention, e.g. mediation and peacebuilding, promoting interaction and exchanges among those sub-groups is necessary for a more comprehensive approach to conflict prevention.

- There is urgent need for reliable data and analysis of conflict prevention that goes beyond case studies and draws on a wide gamut of methodologies, both qualitative and quantitative, combining them with innovative technologies that allow for data interactivity and visualization.

- Knowledge-building and policymaking on conflict prevention should not remain the exclusive or primary province of global powers and associated institutions. The international community should work to boost the role and even protagonism of Global South institutions in generating innovative solutions to conflict prevention based on localized knowledge and collaborative ties among institutions across the developing world.

Bibliography and Resources

ABDENUR, A. E. and G. CARVALHO (2016). Boosting the UN’s Role in Conflict Prevention – What Next?. MUNPlanet, July. Retrieved from: <https://www.munplanet.com/articles/united-nations/boosting-the-uns-role-in-conflict-prevention-what-next>. Accessed July 15, 2017.

ABDENUR, A.E. and R. MUGGAH (2017) “The Conflict Prevention Renaissance: Preventive Diplomacy from a Brazilian Perspective” pp 121-146 in SCHMITZ, G.O. and ROCHA, R.A. (Eds), Brasil e o Sistema das Nações Unidas: desafios e oportunidades na governança global. Brasília: IPEA.

ANNAN, K. (2000). We the Peoples – The Role of the United Nations in the 21st Century. New York: United Nations. Retrieved from: <http://www.un.org/en/events/pastevents/pdfs/We_The_Peoples.pdf.>.

- (2003). Protocol relating to the establishment of the Peace and Security Council of the African Union. African Union. Retrieved from: <www.peaceau.org/uploads/psc-protocol-en.pdf>.

- (2015a). African Peace and Security Architecture: APSA Roadmap 2016-2020. African Union. Retrieved from: <www.peaceau.org/uploads/2015-en-apsa-roadmap-final.pdf. >.

- (2015b). Report of the Chairperson of the Commission on the Follow-Up to the Peace and Security Council Communiqué of 27 October 2014 on Structural Conflict Prevention. African Union. Retrieved from: <www.peaceau.org/uploads/psc-502-cews-rpt-29-4-2015.pdf.>.