Populism is poisoning the global liberal order

January, 2018

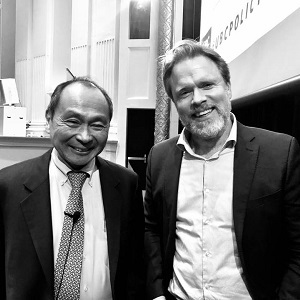

Francis Fukuyama is senior fellow at the Center on Democracy, Development and the Rule of Law, Stanford University. Robert Muggah is the co-founder Igarapé Institute and SecDev Group

Whether springing up in the U.S., Europe or Asia, populists are predictable. Immigrants and elites are usually the first to be targeted by these groups. Populists appeal to “true” citizens to reclaim their homeland, through border walls and trade protectionism. The free press will also come under assault, described by populists as “fake news” and enemies of the truth. Next, the populist will turn his fire on the judiciary and legislative mechanisms responsible for checking executive power.

Notwithstanding global anxieties over populists like U.S. President Donald Trump, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Turkey, and Prime Minister Viktor Orban in Hungary, there is still a surprising level of confusion about what is, and what is not, populism. While there are multiple definitions in circulation, populism can be distilled to three essential characteristics: popular but unsustainable policies; the designation of a specific population group as the sole “legitimate” members of a nation; and highly personalized styles of leadership emphasizing a direct relationship with “the people.”

There is growing consensus that populism constitutes a grave threat to liberal democracy, and to the liberal international order on which peace and prosperity have rested for the past two generations. Democracies rely on power-sharing arrangements, courts, legislatures and a free and independent media to check executive power. Since these institutions obstruct the free reign of populists, they are often subjected to blistering attack. This is especially the case with the right-wing variety of populism that is spreading across the U.S. and Western and Eastern Europe.

The liberal international order depends, in turn, on institutions such as the United Nations, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the World Trade Organization, the G20, the European Union, the North American free-trade agreement and others in order to facilitate the movement of goods and investment across borders. All of them, together with the underlying principles and values giving rise to them, have been in the crosshairs of populist politicians in recent years.

Several factors are enabling the spread of this virulent strain of populism. First there are economic factors associated with the decline of the Western middle class and hyper-concentration of wealth in the hands of the elite. Next are the intrinsic political weaknesses of democracies themselves, dependent as they are on fractious coalitions and divided electorates. These shortcomings are routinely exploited by charismatic strongmen. Just as important are cultural factors related to the resentment of newcomers and the feeling by some that the country has been claimed by foreigners.

These factors explain why immigration, at least in the West, acts as a lightning rod for populism. The surge of migrants and asylum claimants over the past decade – partly a result of failed military interventions in the Middle East and flawed immigration and border controls – has exacerbated anxieties about rapid cultural change in areas of the U.S. and Europe. It is no surprise, then, that identity politics – whether over ethnicity, language, religion or sexuality – is fast displacing class as the defining characteristic of contemporary politics.

The future of the global liberal order hinges in large part on the direction of populism in the U.S. After all, the U.S. was the chief architect and custodian of the world order over the past 70 years. If the U.S. withdraws its support, then the order is likely to come unstuck. There are signs that the U.S.’s constitutional checks and balances are weathering the storm in spite of the best efforts of Mr. Trump. The real question now is whether the President and the Republican Party can maintain their hold on government after the 2018 midterms.

Notwithstanding the threats to Mr. Trump of ongoing investigations into Russian interference in the U.S. elections, there are signs that he could survive the 2018 midterm elections and maybe win a second term in office. The reasons for this can be traced to the fact that the U.S. economy is doing extremely well today. While Mr. Trump cannot claim all the credit for this, the recent Republican tax cut is likely to be seen as a positive contribution to general prosperity despite its adding to long-term fiscal deficits. The steady move of the Democrats to the left of U.S. voters, and their continued focus on identity politics, is a boon for Trump supporters. What matters are not the tweets, but the state of the economy.

It is no exaggeration to say that the fate of the global liberal order hangs precariously in the balance. If the Democrats can regain their majority in the House in 2018 and go on to win the presidency, then Mr. Trump is likely to go down in history as an unpleasant aberration. But if the Democrats lose in 2018 and Mr. Trump wins the presidency in 2020, then polarization in the U.S. will deepen and the savaging of liberal institutions will likely increase. The withdrawal of the U.S. from the global order will continue and power will diffuse from the west to the east. The shift from a uni-polar to a multi-polar world will accelerate, with dangerous fallout.

Even beyond Mr. Trump, there are other reasons why populists post a very real threat to the global liberal order. For one, they regularly play down the systemic changes that are generated by advances in technology. Faced with the massive disruptions that will come about as a result of automation, there are shallow appeals to on-shoring and careless talk of trade wars with China. There are also worrying signs that populists are banding together, as in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland and Serbia, with worrying implications for the integrity of institutions ranging from the UN to the EU and NATO.

One thing is for certain: The road ahead is radically uncertain.

This article forms part of the Phil Lind Initiative in US Studies series on the future of the liberal at UBC’s School of Public Policy and Global Affairs.