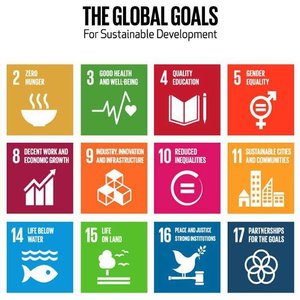

Africa: Unsustainable Development Goals – Are 222 Indicators Too Many?

New York — Are the Sustainable Development Goals in danger of collapsing under the weight of their own lofty ambitions?

As statisticians race to compile a very long list of indicators for the 17 goals and 159 targets by March next year, critics argue that the rush to get it all in place could be a costly mistake. They also worry that countries daunted by the logistical challenge of implementing and measuring the wide-ranging agenda will “cherry pick” goals or even sideline the whole agenda.

Some warn that the immense task of finding the funds, data and tools to measure the many qualitative improvements to people’s lives may overshadow urgent development imperatives. In today’s turbulent world of refugee crises, civil wars and global terrorism, they also discern a waning interest from the media.

Whereas the Millennium Development Goals focused on quantity, the SDGs are all about quality. The number of school graduates, for example, will be less important than whether their education has translated into better job opportunities. But how does a country go about measuring these qualitative changes? The statisticians argue that countries must address this challenge if they want to truly measure real improvements in the lives of their people.

Breakdowns by age, gender and race

In Bangkok last month, the UN-mandated Inter-Agency and Experts Group agreed to a set of 159 “green indicators” attached to the 17 goals and 159 targets. An additional 63 indicators are still in a “grey” zone, meaning there is more work to be done in the months ahead before they get the green light.

Shaida Badiee, manager of Open Data Watch, told IRIN that the Bangkok process (in which she participated) was “as good as it could get,” although she said that due to time constraints only a few minutes were spent on indicators for the last few goals on the list.

Many of the grey indicators will require “disaggregated data”, meaning breakdown categories such as age, gender and race. This is a prerequisite for the central idea that underpins the SDGs of “leaving no one behind”. But Badiee said most statistical tools used to measure development “were devised many years ago and don’t capture this level of disaggregation.”

She argued that it was important for countries to build up their statistical systems, no matter how difficult, if they are to measure progress properly. There is plenty of evidence that better data leads to better decisions and ultimately better delivery, Badiee said, while admitting that the new development framework would put countries under enormous pressure.

It will take even the most advanced countries at least two years to measure their SDG indicators. For those countries that don’t even have statistics available on their websites, getting this information will be a far harder and more time-consuming process.

It will also be very expensive. A study by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network, a UN global initiative led by Jeffrey Sachs, estimates that it will cost $1 billion per year for the next 15 years for 77 low-income countries to bring their statistical systems up to scratch to support and measure the SDGs.

“Mad dash”

Casey Dunning, a senior policy analyst at the Washington-based Centre for Global Development believes the rush to come up with the indicators by March is misguided. “The indicators are what will give the whole new development agenda heft and credibility,” she told IRIN. “It’s a shame to spend three and a half years on goals and targets and let the indicators be decided in a matter of months.”

Dunning said it had taken two years to finalise the MDG indicators and new ones were still being added up to eight years later. Yet the far more complex SDG indicators are being developed in a hurry against “an arbitrary time line”.

Some of the later – and newer – goals, for which indicators were rushed through, such as peace, economic growth and good governance, deserve more time and analysis, she said. “I would have hoped to see a more inclusive and thoughtful process rather than this mad dash to have these indicators out as soon as possible.”

She was also critical of the dizzying number of indicators. Once the grey ones become green, she pointed out, there could be a list of more than 220 indicators. “I can’t imagine going to a finance minister or minister of development planning with a list of (over 200) indicators that they must keep track of annually or quarterly, and not being laughed out of the room.”

Badiee argued that delivery and measurement go hand in hand and that countries will need plenty of support from international agencies, the private sector and NGOs. A “data revolution” is being called for to support the SDGs,

She explained that some indicators measure outcome rather than input and are also about watching over the process. For example, an indicator of Goal 17 says resources must be made available to improve statistical capacity in developing nations.

She also counters criticism from some quarters that there are no measurements to underpin Goal 16 of reducing conflict. Robert Muggah of the Igarape Institute has argued in a study that the Bangkok meeting failed “to agree on even a basic metric or methodology to count conflict deaths. This suits some countries that see the issue as too political. It is also unacceptable,” he said in a newsletter.

“We have 13 green indicators for this goal which try really hard to measure conflict,” said Baidee. “I wouldn’t say this goal is not going to have enough indicators.” However, she added that “more work needs to be done to turn grey areas into green.” For example, finding ways to measure victims of violence – still a grey indicator – will entail disaggregation by age, sex and gender.

Fewer indicators?

Dunning believes there are far too many indicators for countries to take on board and suggest a whittled down list of about 50 minimum priorities. Otherwise, she said, nations will make damaging trade-offs about what they choose to focus on and will end up putting measurement before delivery. “This data can’t be plucked out of thin air – it requires systems and processes and infrastructure. It will mean asking some countries to work on these priorities as opposed to others.”

She said data coverage in many fragile and conflict-ridden states is almost non-existent. “Many of these countries lack data on basics like birth registration and infant mortality. How will they satisfy the new indicators that are asking for so much more?”

Others agreed that the sheer volume of goals, targets and indicators will lead some countries to “cherry pick” their development priorities. This could be an important escape hatch for those countries not keen to tackle more politically contentious and loaded priorities such as gender equity, for example.

Philipp Schönrock, director the Latin American research group, CEPEI, agrees that the task of measuring the SDGs is complex. Given that quality is at the heart of the development agenda “measuring on a multi-dimensional scale” will be required. Although he believes the challenge is “not insurmountable,” he nevertheless sees the lack of human and technological resources to measure the goals as a serious challenge. The danger, he said, is that the SDGs don’t resonate politically and end up losing momentum and strength. The risk of “cherry-picking on the part of countries is the elephant in the room,” he added.

Millennium Institute president Hans Herren was also critical about the rush to get to the finish line, saying the focus on measurement would obscure the more central question of how to get there. “This time round lets do it right, even if it takes a bit longer,” Herren said. Acknowledging the difficulty of getting 193 countries on board, he said that better guidelines, flexibility and tools could enhance the process.

Herren backed the idea of the global framework setting a minimum of requirements but said countries needed to decide for themselves how to get there, in a bottom-up rather than top-down approach. “The framework must be flexible enough to adjust for the specificity of each country. But I’m just not sure they’re addressing this right now.”

Huge savings could be made if countries examined the “roadblocks” in their own delivery systems and stopped duplication and waste, he said. For example, his organisation’s research showed that Ghana would have saved 15 percent of its expenditure on the MDGs if it had better linked its development priorities. Instead, departments tend to work in silos. Countries lacking capacity will find it difficult to harmonise their goals.

“We need much more talk about the process,” said Herren. “We need tools to project different scenarios on how to reach certain goals, which will be different in every country. This is more important before we start taking lots of measurements.”

By Philippa Garson, allAfrica