Where are the world’s most fragile cities?

A handful of cities are booming and rewiring international affairs, but many more are falling behind

Cities, not nation states, are defining the shape and character of security and development in the twenty first century. Decisions being made in fast-growing cities in Africa, Asia and the Americas are determining the future trajectories of everything from climate change to migration.

Although many commentators are mesmerised by the power and potential of 100 or so global cities, virtually nothing is known about thousands of cities that are much less prepared to cope with tomorrow’s crises.

The good news is that a growing number of cities are stepping up to solve major global challenges. Mayors are forging networks within and across international boundaries to address shared problems.

Part of the reason they are doing this is because multilateral institutions and nation states are increasingly unable to solve many of the world’s most intractable issues. The United Nations Security Council and General Assembly are no help, focused as they are on member states rather than cities.

Though a handful of cities are booming and rewiring international affairs, many more are falling behind. In some cases, the social contract that binds urban authorities and citizens is coming unstuck.

When a disequilibrium of expectations occurs between municipal leaders and residents, cities become fragile. An index of fragility is the extent of local service provision – whether public security, health, transportation, or basic utilities.

The world’s most fragile cities are crisscrossed with no-go areas and gripped by extreme volatility. As the cases of Karachi, Kinshasa, and Port-au-Prince demonstrate, hybrid and parallel forms of governance typically emerge.

Militia groups and gangs substitute for the state, including when it comes to delivering basic services to specific neighbourhoods. In cities ranging from Manchester to Mogadishu, local criminal mafias may have more legitimacy than state providers.

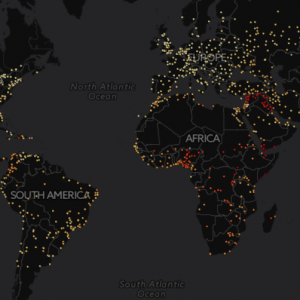

In order to understand the dimensions of city fragility, the Igarapé Institute, United Nations University,World Economic Forum and 100 Resilient Cities developed a data visualisation platform. The consortium focused on 2,100 cities with populations of 250,000 or more. Cities were graded across 11 variables, including population growth rates, unemployment, income inequality, access to basic services (electricity), pollution levels, homicide rates, terrorism-related deaths, conflict events, and natural hazards (including the extent of exposure to cyclones, droughts and floods).

The underlying data for the visualization was gathered from both structured and unstructured sources. Two basic criteria determined the final selection of fragile city indicators: (1) a valid scientific association with city instability and (2) data availability across many cities. A shortlist of indicators was then assembled into a composite scale of 1-4 (with 0 indicating low fragility and 4 indicating high fragility). All of this data was then reassembled into a stunning visualization with the help of xSeer, a data analytics group.

A few interesting facts stand out.

First, city fragility is much more widely distributed than widely assumed. Roughly 14 percent of all 2,100 cities can be considered very fragile (scoring 3-4) including Kabul, Aden and Juba. Another 67 percent of the cities report average levels of fragility (with an index score of 2-3) ranging from St Louis to Valencia. And just 16 percent of all cities report low fragility (0-1) including Canberra, Sarasota and Sakai. Roughly 4 percent of all cities had insufficient data to register a score at all.

Second, most fragile cities are concentrated Africa and Asia, accounting for 93 percent of all high risk settings. Specifically, 44 percent of all African cities are highly fragile and 51 percent experience medium levels of fragility. There are no cities with a low fragility score in Africa. By comparison, roughly 70 percent of Asian cities can be classified as experiencing medium levels of fragility, with a further 15 percent exhibiting the highest levels of fragility.

Third, the regions registering the lowest city fragility include Western Europe, East Asia and North America. Interestingly, there are no highly fragile cities in Europe, while 52 percent of its cities experience medium fragility (2-3) and 47 percent are reported as having low fragility. The Americas – including North, Central and South America – features the highest number of cities with medium levels of fragility (78 percent) and just 4 percent with high rates of fragility.

Fourth, high levels of city fragility are not necessarily confined to low- or even medium income settings. While there are no “high fragility” cities in upper-income countries, there are over 40 high fragile cities in upper middle-income settings, 194 in lower middle settings, and 50 in low-income settings. Even so, there is a comparatively strong relationship between high income and low city fragility and low income and comparatively higher levels of city fragility.

The good news is that city fragility is not permanent. There are positive cases of erstwhile fragile cities turning things around. They start with a clear plan and positive leadership. Ideally, successive mayors stick to a common strategy. Ideally, these cities also build bridges with policy makers at the national, state and municipality levels to align policy strategy and implementation. The most successful cities design proactive partnerships with the private sector and research community to design solutions and measure results.

There are several strategies that help strengthen resilience in even the most fragile cities. Cities that build in inclusive public spaces and invest in areas of concentrated poverty and disadvantage tend to register public security dividends and improvements in collective efficacy.

Investment in more predictable public transport – including bus rapid transit – can also reap long-term social and economic dividends. Municipalities that adopt problem-oriented and evidence -based approaches to policing and create meaningful opportunities for at-risk young people are also most likely to see improvements in safety.

There is also a growing evidence base for ways to reduce the negative impacts of climate risks and natural disasters. City authorities that develop disaster mitigation plans, update zoning legislation and building codes (including provisions for mixed commercial and residential housing), and incubate new technologies to maximize emergency response are more likely to rebound in the face of crisis. A key is to build in mechanisms for local engagement.

City fragility is not a steady state: it is a dynamic set of properties. No city is immune and all cities are fragile to lesser or greater degree. Those that experience an accumulation of risks are most vulnerable. By the same token, cities that invest in mitigating key vulnerabilities today are most likely to thrive tomorrow.

By Robert Muggah

Opinion editorial published in 12 September, 2016

Thomson Reuters Foundation News