The MCI law is fundamentally a digital bill of rights. Its opening articles state that the democratic principles of freedom, privacy and human rights are equally applicable in cyberspace. In particular, Articles 2 and 3 frame these civil rights principles while “acknowledging the global scale of the network”, as well as pluralism, diversity, openness and collaboration and economic rights such as free enterprise, competition and consumer protection. Civil rights take precedence in the legislative language, but free enterprise and new business models are also encouraged “provided they do not conflict with the other principles established in this Law.”

The right to privacy is also guaranteed by the law. Personal data is protected “as provided by the law,” while ensuring that citizens and organizations, both public and private, are accountable according to their activities. Under Article 7, this right to privacy is defined as the “inviolability and secrecy of the flow of the user’s communications through the Internet, except by court order, as provided by law.” Carlos Affonso Souza, Director of the Institute for Technology and Society (ITS) in Rio, participated in the process throughout the development of the MCI in his capacity as a legal scholar at CTS-FGV. He describes how Article 7 became a direct response to Snowden’s revelations of NSA spying, and how this was not the case initially:

First of all, it is important to understand that the MCI was not conceived as tool to tackle the Snowden programs…Because of the scandal, the MCI was changed in a number of ways. Article 7 included privacy and data protection, not only because of the Snowden revelations. [Congressman] Molon realized at the time that the Ministry of Justice had tried to push data protection since 2010 and nothing much happened. At the time, the Marco Civil was looking like a bill with a chance of passing, so they thought that they could take some draft provisions from the data protection bill. One of the main changes relates to data protection and Article 7.

Alessandro Molon, a member of Brazil’s lower house of Congress and sponsor of the Marco Civil, used a legislative maneuver to insert provisions into Article 7 that would compel law enforcement to seek a court order to violate the secrecy of user communications.

In 2015, a conservative block in Congress pushed back against this provision, even as the government continued to determine how the MCI should be implemented. What began as a proposed law to punish “crimes of honor” (such as defamatory or libelous comments on social networks) became a vehicle for an attack on the MCI’s privacy provisions – known formally as PL 215/2015 and by critics as the PL Espião, or “Big Spy Bill”. Opposition members proposed revisions to the civil code and MCI that would require Internet companies to store user data such as name, home address, email and CPF (a Brazilian national ID number). In addition, law enforcement authorities would no longer need to request a judicial order in order to receive this information.

PL 215/2015 was also expected to implement a variation of the European “right to be forgotten” into the law. It would differ from Europe’s legislation, however, where offending content is delisted from search engines like Google. In this case the company hosting the content would be required to remove it from its servers, based on information it collects about every user, such as their real name, national ID number and home address. Affonso of ITS has characterized this debate as “an ongoing conversation reflected in discussions throughout the MCI draft legislation. One side is looking to have human rights-driven legislation in Brazil, but there are repeated attempts to play another round.” Molon put it even more simply: “If approved in this form, PL 215/2015 would practically destroy data secrecy.”

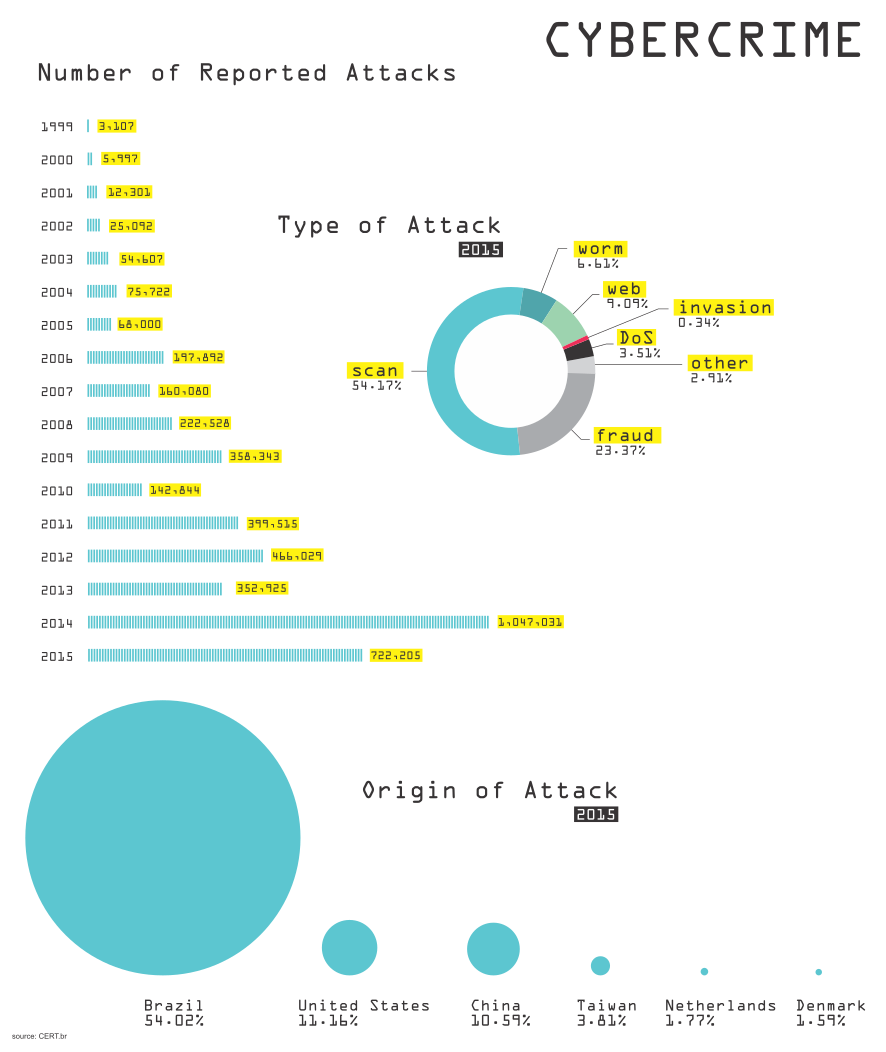

In April of 2016, as the lower house of Brazil’s legislature approved President Rousseff’s impeachment trial and a corruption investigation against senior members of her government and the opposition grew, a special Congressional commission (the Commission of Parliamentary Inquiry on Cybercrime, or CPICIBER) issued a report recommending a series of controversial bills, ostensibly related to cybercrime. These bills include proposals that would enable the expansion of user data retention for applications and Internet providers (PL 3237/2015), or grant access to IP addresses in criminal investigations without a judicial warrant (PLS 730/2015). PL 5204/2016 would permit the blockage of sites at the root level. Another could penalize online security researchers for testing malware. PL 5203/2016 would increase penalties for infringement of copyright, and for hosts that do not quickly take down illegal content. The authors of the MCI specifically excluded copyright from the law – and it remains a section of the Brazilian legal code in need of reform – but the commissioners appear intent on taking a punitive tact. This approach would be in alignment with more extreme copyright enforcement regulations, such as the U.S. Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA).

Finally, CPICIBER proposes paying for these initiatives by appropriating money that is generally earmarked for the development of infrastructure to support universal Internet access (the Fistel telecommunications fund) and re-allocating it towards police investigations and other security operations. The ambitious scope of these proposals, which seek to modify already implemented aspects of the MCI, highlight the commission’s desire to revisit the more punitive objectives of the cybercrime bill that inspired the MCI (i.e. Azeredo’s Law). As a digital bill of rights, a primary objective of the MCI was to contest the penal approach to cybercrime with the construction of a broader legal framework defining rights and responsibilities for individuals and organizations.

Abramovay described this framework, and the Ministry’s approach:

Our position was against punitive criminal law and ‘law and order’ perspectives on many issues – from alternative penalties, to drug policy and many others. The [MCI] process was part of this perspective, the civil rights perspective for criminal law. Because we took this position, civil society came closer to us during this process, and we had no particular expertise within the ministry to discuss Internet and telecommunications issues.

Later, the Ministry of Justice worked with the Ministry of Culture to develop the online open source system that drafted the bill, and consulted closely with CTS-FGV on the initial text and the integration of the subsequent comments and feedback. Groups that back the “law and order” position have the support of President Temer’s allies in Congress; the CPI Cybercrime bills, PL 215/2015 and challenges to full MCI implementation are all indicators of this continued opposition.

Brazilian and international civil society groups have criticized these proposals and accompanying challenges to the law, including the CPICIBER commission recommendations. An open letter to Brazil’s Congress, signed by Brazilian and international organizations ranging from Access Now and the Electronic Frontier Foundation to ITS, CTS-FGV and the Igarapé Institute, articulated the main concerns:

The bills in this report and the report itself would criminalize the practices of ordinary Internet users under the pretext of preventing cybercrimes. We urge the Brazilian Congress to continue standing for Internet Freedom. Congress should drop the draft bills proposed by the Commission of Parliamentary Inquiry on Cybercrimes (CPI dos Crimes Cibernéticos) and continue to focus on advancing an open and free Internet.

Conversely, the MCI does not provide explicit descriptions of penalties, methods and user safeguards for personal data protection, which the law calls for the President’s office to develop. Data is the currency of our age; it is the lifeblood of nearly every country and company, from China to Facebook. It is therefore critical to have open discussions and debates on how data is defined and codified within a country’s legal system. How should companies approach and handle data? What should organizations do to protect data, how can users ensure it is being stored properly and how does the law distinguish between different kinds of digital information (e.g. anonymized, meta or personal)?

In early 2015, the Brazilian Ministry of Justice began taking public comments on a draft law for data protection. The government received 1,200 comments from a wide variety of groups, including private sector companies, non-profit organizations and individual citizens. After the open comment period, the legislature has moved to develop its own proposals focused on data protection. Senators from the Committee on Science and Technology and another senator who headed the committee investigating espionage in the country in 2014 developed versions of the law. The objective of these efforts is to prevent the commercialization and misuse of personal data.

On May 12, 2016, the same day the Senate approved President Rousseff’s impeachment trial and suspended her from office, Rousseff sent a new version of the data protection bill (PL 5276/2016) to two lower house committees: The Committee on Justice and the Constitution, and the Committee on Labor, Public Service and Administration. This draft bill would sanction the use of data only with the permission of Internet users and for the execution of specific purposes they define. The bill also proposes to create an authority to implement and monitor a protection regime, providing users with mechanisms to report infringement of the regulation. Rousseff’s office noted that such a proposal for a new bureaucratic administration could only emanate from her office, suggesting another reason for her urgent order on the day. Civil society groups were largely supportive of the new bill, which was drafted by integrating extensive public comments and demands for robust privacy protections.

Questions of data protection, privacy and security predate the passage of the MCI. In terms of the penalties for non-compliance, Rousseff’s May data protection proposal is stronger and more narrowly-defined than earlier proposals, such as PL 4060/2012 or the Senate drafts. Two cybersecurity laws are directly connected to the MCI – Azeredo’s Law (Law 12.735/2012) and Carolina Dieckmann’s Law (Law 12.737/2012). The latter is named for a celebrity whose nude photos were leaked over the Internet after hackers broke into her personal computer; the former is a general modification of the penal code to specify electronic crimes, named for Senator Eduardo Azeredo, the sponsor of the bill since 1999. The MCI itself was, in part, a critical response to Senator Azeredo’s cybersecurity law. As with more recent proposals, such as PL 215/2015, legal scholars and civil society groups criticized Azeredo’s bill as being too punitive and focused on protecting the interests of the wealthy and powerful. The law sanctioned increased penalties for crimes against public figures, such as politicians and wealthy entrepreneurs.

While this proposed cybersecurity law was being debated in 2007, Ronaldo Lemos, a legal scholar and co-founder of the Institute of Technology and Society (ITS) in Rio de Janeiro, authored a widely-read editorial that jump started the MCI process. Lemos argued that policymakers could not define Internet crimes in the penal code without corresponding rights and responsibilities for individual citizens, companies and government agencies online. Security, as well as concerns about government overreach and online digital rights, were at the heart of the draft legislation from the outset.

Nonetheless, both security laws were enacted in 2013, a year before the MCI. Their passage was prompted in large part by the leaked Dieckmann photos and subsequent media coverage. The Dieckmann law addresses invasions of privacy and the protection of personal data, making it a crime to “obtain, tamper with or destroy data or information without the expressed or tacit authorization of the owner of the device, or install vulnerabilities” to achieve these ends. The statute contains language that increases penalties for decrypting or accessing private electronic communications that are commercial, industrial or governmentally defined secrets, significantly boosting fines and jail time for such crimes. Interrupting or tampering with telecommunications of any kind is now an indictable offense, punishable through the civil code.

However, these laws highlight the contradictions between strong privacy protections and the criminalization of online behavior. Dieckmann’s law in particular differentiates between citizen data, and data possessed by the government and private businesses. This is a concern of legislators, who sometimes use laws like Dieckmann’s and the proposed PL 215/2015 to gain special protection under the law as public figures. The so-called “right to be forgotten” is an example. “There are at least five bills that have been introduced into the Congress [in 2015], and none of them exempts politicians or authorities from the scope of the right to be forgotten,” noted Affonso in an interview. In 2016, as battles over corruption and impeachment turned into highly visible affairs, politicians have shown themselves as particularly eager to have ways of protecting their image online. Lemos, one of the principal drafters of the MCI, says these types of protective legal mechanisms do not have a place in a democracy: “In democratic countries (and also in Brazil), public figures, especially those holding elective office, have a lower threshold than the general public in terms of defamation of character. It is vital that this is so, to allow continual scrutiny.”

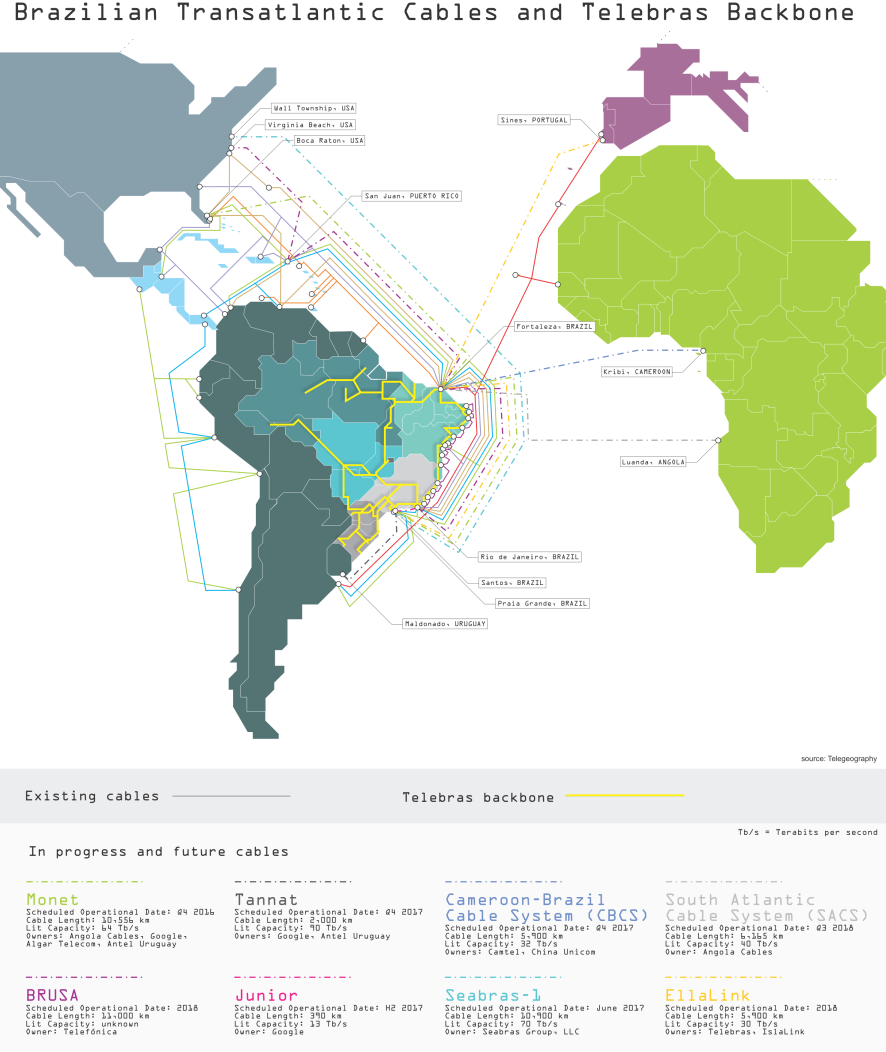

At the same time, the judiciary and law enforcement, backed by conservative legislators, have advocated for increased access to user data by any means necessary. During the deliberations to draft the MCI in 2014, legislators proposed a provision that would force all multinational Internet companies to store data locally on servers in Brazil. While this initiative was ultimately defeated, it mirrored proposals put forth in countries such as Russia and Turkey that have been moving towards more authoritarian systems of government.

The competing goals surrounding user privacy and public security policies gained headlines in December 2015, when a São Paulo judge ordered the shutdown of instant messaging service WhatsApp for 48 hours, because its parent company, Facebook, refused to turn over user data for investigations into drug tracking and organized crime. A higher court overturned the ruling less than 13 hours later, but the episode demonstrated how intent investigators are in gaining access to personal communications. Law enforcement officials have found allies in the telecoms that have to respond to court-ordered requests for data; Brazilian mobile operators increasingly view WhatsApp – and other over-the-top (OTT) messaging services, such as Telegram – as a threat to traditional SMS messaging, for which they charge fees and are heavily regulated. In the past, groups such as Vivo (owned by Spain’s Telefonica) and Oi filed appeals against such shutdowns, but in the December 2015 WhatsApp shutdown, only Oi made such an appeal.

In 2015, the president and CEO of Telefônica Brasil, which owns Vivo, called WhatsApp “pirates”, criticized its business model as leeching off of telecoms’ investment in the networks and demanded that ANATEL regulate such services as they do telecoms that provide SMS or traditional telephony. Marília Maciel, Director of CTS-FGV at the time, noted in an interview that regulating such services in this way conflicted with the principle of net neutrality and other provisions of the Marco Civil:

By asking the telecom providers to block WhatsApp, the judge put them in a difficult situation. With each blockage, telecoms may be in contravention of the principles of network neutrality. It was a very unfortunate decision. It did not meet the basic principles of proportionality, and it hampered the ability for Brazilian citizens to communicate freely. It’s a real problem that needs to be confronted…it’s an incentive for public authorities to say “let’s localize data.”

This conflict has grown more pronounced in the contested political environment and with a new president with different policy goals and priorities. As the CPICIBER congressional commission debated the final version of its cybercrime report in April, a judge in the state of Sergipe ordered another shutdown of the WhatsApp service – this time for 72 hours. The action – and the outcry of digital rights groups – prompted the commission to include language preventing the blanket shutdown of social networks, even curtailing aspects of the MCI that impose network shutdown penalties for Internet companies that do not comply with judicial orders.

The modifications did not change the punitive nature of the newly proposed laws, however, nor did they address the potentially broadened authority of law enforcement to investigate and shut down users online. Some civil society groups argued that this order contravened the MCI’s network neutrality provisions, in that it blocked a specific kind of traffic; an appeals judge rescinded the shutdown after 24 hours, short of the 72 mandated by the original court order. In March, another judge in São Paulo had attempted a different approach, briefly jailing Diego Dzodan, the vice president of Facebook for Latin America, in another effort to force WhatsApp to provide data for an ongoing criminal investigation. In July, WhatsApp was blocked for a third time in seven months by a judge in Rio de Janeiro state, though service was restored when the judicial order was overturned by Brazil’s Supreme Court. Unlike the earlier two blocks, the Rio de Janeiro judge did not ask for previous communication logs, but for real-time monitoring of encrypted communications of a suspect, demonstrating a lack of understanding of how end-to-end encrypted messaging functions. The judge’s action prompted calls for a more open dialogue between the Ministry of Justice and digital rights groups on the laws governing such wiretaps and the nature of the technology used.

These judicial blocks and the detention of a Facebook executive highlights the contentious nature of the present environment in Brazil and the frustration of many political, judicial and law enforcement actors to accept new cryptographic systems imposed by foreign companies in their products. WhatsApp had been steadily integrating a new end-to-end encryption backbone since Edward Snowden’s revelations about NSA surveillance activity in 2013. The company significantly deepened its expertise in this area by hiring cryptographers from Open Whisper Systems (developers of Snowden’s messaging app of choice, Signal), completing full implementation across platforms for its one billion users in April 2016. Despite the Rousseff administration’s commitment to stronger encryption and alternative systems within the government as a wedge against U.S. dominance of international networks, members of her government, law enforcement, opposition, and members of the judiciary continued to challenge privacy, freedom of expression and civil rights principles in a pursuit to ensure greater security.

A struggle of political forces, security services and civil society is embedded in the history of the MCI. It began with debates over Azeredo’s draft law going back to the 1990s, and continued in struggles over the MCI’s implementation, with especially contentious arguments between telecom providers and Internet companies such as Facebook, WhatsApp and Google over data protection and localization, and repeated attempts in Congress to amend articles of the law dedicated to privacy. The NSA eavesdropping scandal bolstered the case of human rights and privacy advocates, strengthening the draft legislation’s core provisions, but once the scandal faded and the Rousseff administration made peace with the U.S. government, Dilma appeared unwilling to push for greater privacy rights in public. At the same time, the opposition to the president grew, and completely paralyzed the government by the time of Rousseff’s removal from office in May 2016. Responding directly to the WhatsApp blockage, members of Congress proposed new bills (such as PL 5172/2016 and PL 5130/2016) that would prohibit social network shutdowns, integrating suggestions from CPICIBER. A more recent proposal has challenged the constitutionality of Article 12 of the MCI, which calls for the suspension of services that do not comply with the law’s data retention and provision in cases of law enforcement requests, as defined by Articles 10 and 11. Some lawmakers and judges have said these articles could be used to justify future blockages. Finally, a proposal circulating in late 2016 (PL 5402/16) would provide legal justifications for shutting down social networks for any crime punishable by more than 2 years in prison. It is particularly driven by copyright holders as a means to shutdown social networks for unauthorized content. While the MCI does not address copyright, it remains a key concern of the private sector and their trade organizations, supported by Temer’s administration.

At a conference on privacy and data protection in August 2016, Affonso, the Director of ITS, commented that in his reading, the MCI did not sanction these kind of blockages. “The sanctions in Article 12 includes these activities, but not the complete suspension of activities of an application”, he observes. “It is understood that the judge has a prerogative to suspend or block an application, but the power of the judge needs to pass a test of proportionality. It is not an absolute power. Thus, you have two ways to try to prevent a complete shutdown: by appealing that this power doesn’t appear in the MCI, and that the power in general of the judge needs to appeal to this test.” Affonso also noted that the head of the Supreme Court had ended the blockages quickly, ruling that they were not proportional and infringed on the rights of freedom of expression for millions of Brazilians. In October 2016, ITS entered an amicus curiae brief with Brazil’s Supreme Federal Tribunal, arguing that such judicial blocks of applications and services in the Internet’s infrastructure layer are a direct violation of the MCI.

Over the past year, Brazil has witnessed competing impulses to pursue copyright infringement and give prosecutors more power to pursue investigations while allowing freedom of expression and preventing large-scale blockages as in the WhatsApp case. In this atmosphere, Rousseff’s rivals in Congress, backed by members of the judiciary, law enforcement and of the intelligence services, consolidated their efforts to scale back the privacy protections of the MCI with PL 215/2015, CPICIBER and resisting certain aspects of the MCI’s implementation.